Abstract

Carbon monoxide intoxication is the most prevalent cause of death from carbon monoxide poisoning. We herein report the case of a 56-year-old man who was found unconscious and smelled of smoke after exposure to carbon monoxide from a heater. He scored 5 on the Glasgow Coma Scale, and had respiratory insufficiency and elevated troponin I, creatine kinase-MB fraction and carboxyhaemoglobin levels. He was treated by mechanical ventilation. After regaining consciousness, brain magnetic resonance imaging showed diffusion restriction in the left occipital lobe; there was a loss of vision (right temporal hemianopsia), which improved by the follow-up session. Carbon monoxide intoxication may cause neurologic and cardiac sequelae, and the initial treatment includes oxygen therapy. Acute carbon monoxide poisoning can cause serious injury to the brain, heart and other organs; the most severe damages that could be inflicted to the brain include cerebral ischaemia and hypoxia, oedema, and neural cell degeneration and necrosis.

INTRODUCTION

Carbon monoxide is a colourless, odourless, tasteless, non-irritating but poisonous gas that is produced when carbon-based fuels and particles burn without sufficient air.(1) Carbon monoxide may cause hypoxia by hindering the delivery of oxygen to tissues because it binds to haemoglobin with a 250-fold greater affinity than oxygen to form carboxyhaemoglobin. Carbon monoxide intoxication is the most prevalent cause of death from carbon monoxide poisoning.(2) The central nervous and cardiovascular systems are most susceptible to hypoxia associated with carbon monoxide intoxication, and neurologic sequelae are among the most common problems that occur after exposure to carbon monoxide.(3) Following carbon monoxide intoxication, patients may develop headache, confusion, dizziness, visual impairment, nausea, vomiting, malaise, psychological lability, lethargy, somnolence, stroke, coma, arrhythmia, and cardiac arrest.

We herein report the case of a patient who was successfully treated after losing consciousness and vision as a result of carbon monoxide intoxication. Although he regained consciousness after four days of mechanical ventilation, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the brain showed diffusion restriction in the left occipital lobe.

CASE REPORT

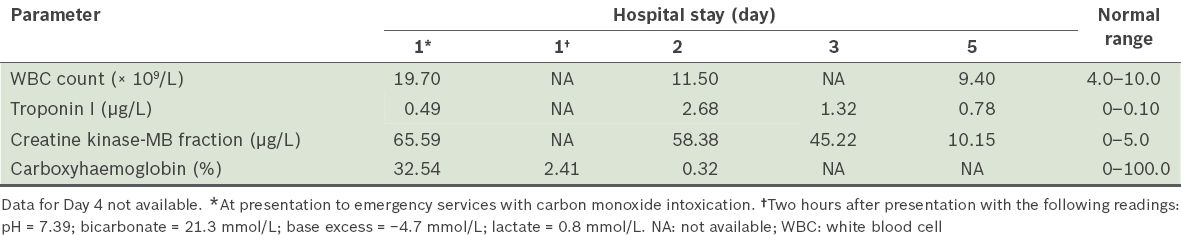

A 56-year-old man was exposed to carbon monoxide from a heater at home. He was found by his relatives and taken to the emergency department of our hospital. His wife, also poisoned by carbon monoxide, was found dead. On examination, the patient was found to be unconscious, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 5. He also had respiratory insufficiency and his body emitted an odour of smoke. Initial treatment included endotracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation, and administration of diuretics and antiplatelet drugs. Laboratory test results showed elevated white blood cell count and levels of troponin I, creatine kinase-MB fraction and carboxyhaemoglobin (

Table I

Laboratory test results of the patient.

The patient was treated in the intensive care unit. Carboxyhaemoglobin level improved from Day 1 to Day 2 of hospital stay, while the levels of troponin I and creatine kinase-MB fraction improved from Day 1 to Day 5 (

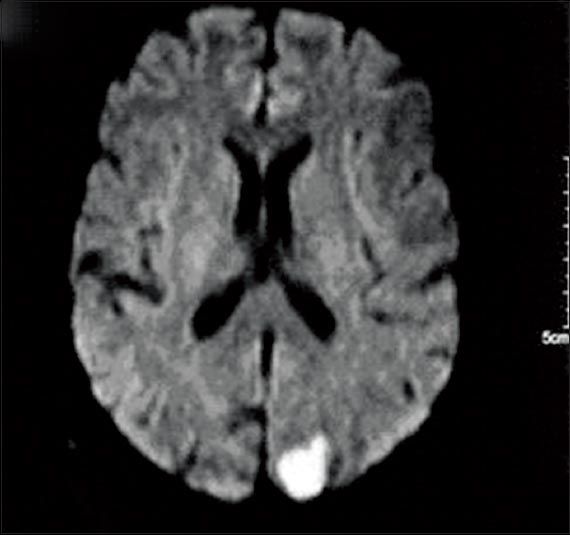

Fig. 1

MR image of the brain shows diffusion restriction in the left occipital lobe.

The patient was discharged on Day 8 of hospitalisation. Follow-up at the neurology clinic showed that the loss of vision resolved in three weeks after the carbon monoxide exposure.

DISCUSSION

The patient had carbon monoxide poisoning, which caused respiratory insufficiency, neurologic changes (loss of consciousness and visual impairment) and cardiac dysfunction (elevated troponin I, creatine kinase-MB fraction and carboxyhaemoglobin levels, and left ventricular dysfunction). Visual field defect is a significant outcome of occipital lobe infarct,(4) and the diffusion restriction observed in the left occipital lobe of our patient is evidence that the vision loss resulted from an occipital lobe ischaemic infarct.

Carbon monoxide inhibits the mitochondrial electron transport system and activates polymorphonuclear leucocytes that cause brain lipid peroxidation. This process may explain the delayed outcomes of carbon monoxide intoxication such as late encephalopathy.(5) Acute brain injury in patients exposed to carbon monoxide is usually caused by hypoxia. Neurons normally require major amounts of oxygen and glucose, and they are the cells in the central nervous system that are most vulnerable to the effects of ischaemia and hypoxia. Acute carbon monoxide intoxication causes diffuse hypoxic and ischaemic encephalopathy, primarily in the grey matter; the temporal lobe and hippocampus are more commonly affected than the cerebral cortex.(6) There may be temporal lobe oedema or infarction before cerebral artery occlusion, and focal or general neuroanatomic abnormality may be seen on MR imaging and computed tomography.(5) Delayed neurologic disorders may occur in older patients and are rare in younger patients.(7)

The most common manifestations of carbon monoxide intoxication on brain MR imaging include bilateral globus pallidus and white matter lesions, especially in the periventricular area.(8) Acute demyelination, subcortical white matter damage, and cerebral atrophy may occur. Focal structural lesions may be noted in the thalamus, hippocampus, white matter and basal ganglia.(9) Neuropsychiatric defects such as dementia, personality changes, psychosis, parkinsonism and incontinence may be observed in 10%–30% of patients after carbon monoxide intoxication.

Hyperbaric oxygen treatment may be required in patients who have severe carbon monoxide intoxication or carboxyhaemoglobin level > 0.25. Carbon monoxide elimination can be achieved in 300 min with room air, 80 min with 100% oxygen, and 23 min with hyperbaric oxygen.(10) Neurologic sequelae of carbon monoxide intoxication may be more frequent in children and elderly patients, and oxygen therapy should be started as soon as possible. Although our patient was unconscious and had an elevated carboxyhaemoglobin level and a low Glasgow Coma Scale score, hyperbaric oxygen was not used because it was not available in our hospital. Hon et al(11) reported visual loss related to carbon monoxide poisoning in three patients, with spontaneous recovery after a few days and recovery to near-normal levels after three weeks in all three patients. Similarly, our patient’s visual loss symptoms resolved spontaneously within a short period. He started to show significant improvement after the initiation of 100% oxygen with mechanical ventilation, most probably due to the concentrated oxygen.

Carbon monoxide intoxication may cause cardiopulmonary problems that are associated with hypoxia, including myocardial ischaemia, ventricular arrhythmia and pulmonary oedema. In addition, carbon monoxide may have a direct toxic effect on the myocardial mitochondria. Cardiac symptoms may occur immediately or several days after carbon monoxide exposure, and include palpitations, sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, ventricular extrasystole, and bradycardia.(12) Angina pectoris and myocardial infarction may occur in patients who have ischaemic heart disease. Delayed effects of carbon monoxide intoxication, which may occur 2–40 days after carbon monoxide exposure, may also involve the central nervous system. In this case report, the high troponin I level was likely caused by myocardial ischaemia secondary to carbon monoxide intoxication.