Abstract

Deliberate self-harm refers to an intentional act of causing physical injury to oneself without wanting to die. It is frequently encountered in adolescents who have mental health problems. Primary care physicians play an important role in the early detection and timely intervention of deliberate self-harm in adolescents. This article aims to outline the associated risk factors and possible aetiologies of deliberate self-harm in adolescents, as well as provide suggestions for clinical assessment and appropriate management within the primary care setting.

Lyn, a 17-year-old student, came to see you for frequent headaches. She was quiet and avoided eye contact while her mother was telling you about her increasing withdrawal at home. You noticed that Lyn’s left wrist had multiple slash scars that were recent and healing. You asked Lyn’s mother to wait outside so that you could speak with her alone. Lyn then shared that she had been cutting herself with a penknife whenever she felt stressed. You initially considered dismissing this as a case of teenage angst but decided to ask a few more questions to ensure the patient’s safety and to exclude a more serious condition.

WHAT IS DELIBERATE SELF-HARM?

Deliberate self-harm refers to an intentional act of causing physical injury to oneself without wanting to die. Deliberate self-harm behaviours most commonly include cutting (with a knife or razor), scratching or hitting oneself, and intentional drug overdose. They may also include limiting of food intake and other ‘risk-taking’ behaviours such as driving at high speeds and having unsafe sex.(1,2) Many individuals who self-harm use more than one method of self-injury. These acts are often gratifying and cause minor to moderate harm. Some individuals self-harm on a regular basis, while others do it only once or a few times. Although deliberate self-harm is done without lethal intent, it could lead to fatality.

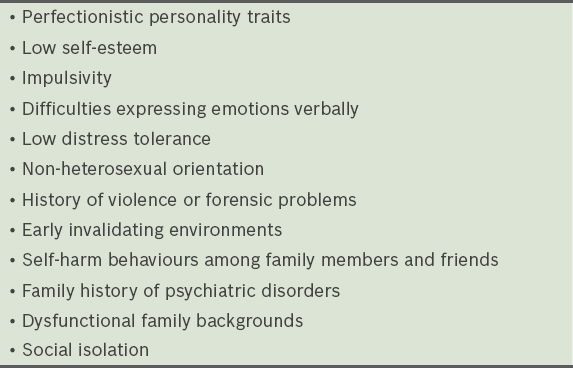

WHO IS AT RISK?

Deliberate self-harm is a significant clinical problem, especially among younger people in Singapore. It has been found to be positively associated with the female gender, mood disorders, adjustment disorders and regular alcohol use.(3)

WHY DO ADOLESCENTS SELF-HARM?

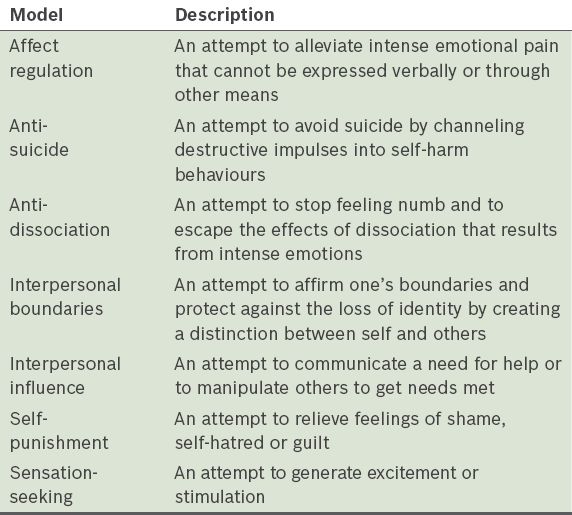

In the current literature, several models have been proposed to outline why individuals engage in deliberate self-harm.(2,5,6) These models are not mutually exclusive, and each describes deliberate self-harm as an attempt to cope with intense emotional states (

Table II

Models of deliberate self-harm.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

Assess for self-harm behaviours and associated psychiatric conditions

If you suspect an adolescent patient is engaging in deliberate self-harm, it is important to assess for the presence of self-harm as well as other salient features of the act, including precipitating factors, frequency and lethality of the method. Primary care physicians are also urged to familiarise themselves with common psychiatric conditions that tend to accompany deliberate self-harm behaviours in order to rule out the presence of these conditions. They include (a) acute stress disorder or adjustment disorder; (b) depression, in particular, the presence of suicidal ideation; (c) anxiety disorders; (d) post-traumatic stress disorder; (e) psychosis; and (f) learning difficulties.(7)

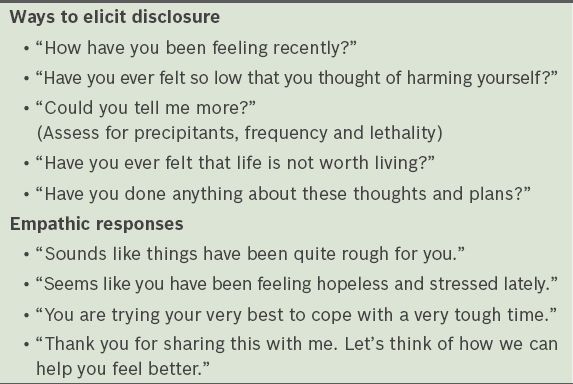

Provide empathic listening

Empathic listening is the process of listening so that others are encouraged to talk; this is especially crucial for adolescents, who often feel unheard and misunderstood.(8) Primary care physicians can facilitate engagement with adolescent patients by creating a safe space for them to freely discuss their problems without interruption. Adolescents may be more willing to disclose their struggles when they are interviewed alone or given time to open up and when they know that their right to patient confidentiality is respected.

As deliberate self-harm is a coping method, focusing solely on condemning or stopping the act can be detrimental. Advice on harm minimisation (such as keeping cutting objects sterile and having first aid supplies at home) is more helpful when the adolescent has learnt alternative self-soothing methods. In addition, a majority of adolescent patients feel ashamed of or disgusted with the act of self-harm and often worry about the negative judgement of others. Therefore, primary care physicians should demonstrate an empathic stance. They can help their adolescent patients feel understood by using simple reflections to validate their emotional experiences and by withholding negative judgements of their self-harm acts.

Table III

Ways to elicit and respond to disclosure of deliberate self-harm.

Provide brief problem-solving advice

Primary care physicians can also provide their adolescent patients with brief problem-solving advice after they have identified the stressors. This may include: (a) suggesting alternative self-soothing ways to improve their moods (such as exercising, engaging in hobbies or listening to calming music); (b) helping them to identify solutions to their prevailing predicament, as well as listing down the advantages and disadvantages of each solution; and (c) identifying supportive individuals whom they can reach out to for support during times of distress (such as family members, classmates or friends). Primary care physicians should also provide adolescent patients with details of local helplines and resources that are available in the community (

Table VI

List of local helplines.

Provide parental education

Primary care physicians also play an important role in educating family members about deliberate self-harm and modelling a compassionate approach to talking about self-harm to adolescents. Many parents tend to seek a quick fix for the self-harm act, but it is important for them to adjust their expectations about recovery. Advice for parents or caregivers of adolescents who self-harm:

Remain calm and validate the emotional experiences; Do not punish them for the self-harm act, as this may deepen guilt or shame; Do not push them to talk if they do not feel comfortable to; Focus on the underlying struggles rather than the act of self-harm; Encourage and model healthy ways of coping with stress; Praise them for their strengths and resourcefulness; Allow them time to learn alternative self-soothing methods to replace the self-harm behaviours; Seek assistance and support from school counsellors, child and adolescent psychiatrists or psychologists, or social workers at family service or counselling centres.

Refer to specialist care

For adolescent patients presenting with more severe psychiatric conditions or who have poor responses to initial treatment within the primary care setting, referral to a specialist or other allied healthcare colleagues can be considered. A referral for psychiatric hospitalisation is indicated for high-risk patients presenting with the following: (a) strong suicidal intent or plan, or a recent suicide attempt; (b) severe psychiatric conditions such as psychosis; and (c) high frequency, intensity and lethality of self-harm acts. A referral for formal psychotherapy may be helpful for adolescent patients to address underlying psychological issues and to develop more effective coping skills in regulating emotions and tolerating distress.

Lyn explained to you that her stress had been caused by longstanding difficulties communicating with her parents, who were opposed to her relationship with her boyfriend. Lyn denied suicidal thoughts and maintained that she was still interested in her social and academic pursuits. You validated Lyn’s emotional experiences and helped her to recognise that self-harm was not a long-term solution to her problems. You encouraged her to explore ways to cheer herself up and to communicate her feelings of distress to her parents. You reassured her that if her initial attempt at talking to her parents did not go well, you could arrange a session to meet them together. You also offered to refer her to a psychologist to learn more effective emotion regulation and assertiveness skills. Lyn appreciated you for taking time to listen to her problems and felt that your compassionate responses had given her motivation to work on some of the suggested ways to better cope with her stressors.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Primary care physicians play an important role in the early detection and timely intervention of deliberate self-harm in adolescents.

-

Deliberate self-harm can be dangerous and should be taken seriously.

-

Primary care physicians should be familiar with the associated risk factors and common psychiatric conditions that increase the risk of deliberate self-harm in adolescents.

-

Deliberate self-harm may serve one or more different functions.

-

Non-judgmental empathic responses to a disclosure of self-harm help adolescent patients feel that they are heard and may lead to a greater willingness to talk about their problems.

-

Primary care physicians play an important role in educating family members about deliberate self-harm and modelling a compassionate approach to recovery.

-

Referral to specialist care is indicated for adolescent patients with more severe psychiatric conditions or poor responses to initial treatment.

RECOMMENDED READING

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Claes L, Vandereycken W. Self-injurious behavior: differential diagnosis and functional differentiation. Compr Psychiatry 2007; 48:137-44. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. (2004). Self-harm: The short-term physical and psychological management and secondary prevention of self-harm in primary and secondary care. NICE Guidelines, July 2004.