Abstract

In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), the human body is divided into Yin and Yang. Diseases occur when the Yin and Yang balance is disrupted. Different herbs are used to restore this balance, achieving the goal of treatment. However, inherent difficulties in designing experimental trials have left much of TCM yet to be substantiated by science. Despite that, TCM not only remains a popular form of medical treatment among the Chinese, but is also gaining popularity in the West. This phenomenon has brought along with it increasing reports on herb-drug interactions, beckoning the attention of Western physicians, who will find it increasingly difficult to ignore the impact of TCM on Western therapies. This paper aims to facilitate the education of Western physicians on common Chinese herbs and raise awareness about potential interactions between these herbs and warfarin, a drug that is especially susceptible to herb-drug interactions due to its narrow therapeutic range.

INTRODUCTION

Warfarin is an anticoagulant that is widely prescribed for chronic atrial fibrillation, mechanical valves, deep vein thrombosis and recurrent stroke.(1,2) Patients on warfarin are often maintained on long-term therapy; hence, a substantial number turn concurrently to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for synergistic effects. This, coupled with the narrow therapeutic range of warfarin, renders these patients particularly susceptible to adverse outcomes from herb-warfarin interactions. Patients on warfarin are regularly monitored using the international normalised ratio (INR), of which a target between 2.0 and 3.5 is desired, depending on its indications. While the role of dietary changes in causing INR fluctuations is often discussed, little attention has been paid to the role of herbal medicines in altering the effects of warfarin.

The problem of herb-drug interaction is one that is pertinent. Firstly, TCM use is prevalent. A survey of a Singapore housing estate in 2005 showed that 76% used complementary medicine over the past year, of which TCM was the most common.(3) Secondly, a significant proportion, estimated at 26.0% and 23.5% in Hong Kong and Italy, respectively, co-ingest warfarin and Chinese herbs.(4,5) Thirdly, there is widespread undisclosed use of complementary medicine among Western doctors, which studies in Singapore and Italy have estimated at rates of 75.4% to more than 90.0%.(3,4) Therefore, there is a need for practitioners to recognise the need to actively elicit the use of complementary medications from patients. This is especially important as most over-the-counter herbs,(3) the commonest mode of complementary medicine use, do not contain key safety messages, such as that of herbal interaction with Western medications.(6)

Warfarin works by inhibiting vitamin K epoxide reductase, preventing the recycling of vitamin K, which is needed to activate clotting factors II, VII, IX and X. These clotting factors are required for the formation of fibrin.(1,2) Warfarin is orally administered in the form of R- and S-warfarin, of which S-warfarin is 3–5 times more active than R-warfarin. S-warfarin is mainly metabolised by CYP2C9; other enzymes include CYP2C8, CYP2C18 and CYP2C19. R-warfarin is mainly metabolised by CYP1A2 and CYP3A4; other enzymes include CYP1A1, CYP2C8, CYP2C18, CYP2C19 and CYP3A5.(2)

Interaction between warfarin and Chinese herbs can be classified into pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interactions. Pharmacokinetic interactions affect the absorption, distribution, metabolism or elimination of a drug. Pharmacodynamic interactions result from synergistic or antagonistic effects of herbs on drugs.(7) This paper aims to consolidate the available literature for and against the interactions between commonly used Chinese herbs and warfarin. This can, firstly, serve as a resource to help guide medical practitioners in counselling patients on the use of warfarin, and secondly, identify gaps in existing evidence.

METHODS

A recently published review article(8) was consulted for a list of Chinese herbs with known or potential interaction with antiplatelets or anticoagulants, with the addition of other herbs known in TCM to invigorate blood circulation and stop bleeding. Of these, 44 Chinese herbs and supplements commonly used in Singapore were included in our study. A search was conducted in both English (PubMed) and Chinese (Wanfang Med Online) databases. Wanfang Med online is an established database that displays selected top Chinese medical journals in China. The MeSH headings and keywords were: warfarin or antiplatelet or anticoagulant or cytochrome P450, and the English, Chinese or Latin names of each Chinese herb. Bibliographies of the papers were also referred to for other relevant studies. All studies with relevant titles were retrieved and selected based on their abstracts. In view of the limited research papers in this area, all forms of publications, including randomised controlled trials, crossover studies, case reports, animal studies and in vitro studies, were selected. Studies involving herbal formulae were excluded. Studies over a 30-year period from 1983 to 2014 were included. Only articles involving warfarin were selected, with the exception of herbs that yielded no articles on interaction with warfarin. In such cases, interaction of the herb with other antiplatelets or anticoagulants was included in view of possible extrapolations, and such cases were highlighted.

Articles were selected independently by two authors based on title and abstract. The selected articles were approved by the two senior authors (an experienced TCM physician and an established Western physician with special interest in TCM) before the results were consolidated. The articles were analysed and the data was organised into an excel document for easy reference. Relevant data extracted included the study methodology, evidence and mechanism of interaction, and other information such as plant parts as well as herb and warfarin dosages, if available. The results were continually reviewed by the two senior authors and two other non-authors (an established Western practitioner and a senior Chinese physician) during meetings.

A total of 107 articles were selected based on title and abstract. Of these, only articles with full texts available were selected. A total of 77 articles were included: 13 case reports, 14 human studies, 21 animal studies and 29 in vitro studies. Of the human studies, two were randomised controlled studies and six were crossover studies. Given the limited number of randomised controlled studies available in this area, other articles (case reports, human studies, animal studies and in vitro studies) had to be included in the data analysis. The type of study from which each piece of evidence was obtained was included in the collated table of results for the reader’s reference.

RESULTS

The information gathered from the search has been classified into four tables for easy reference.

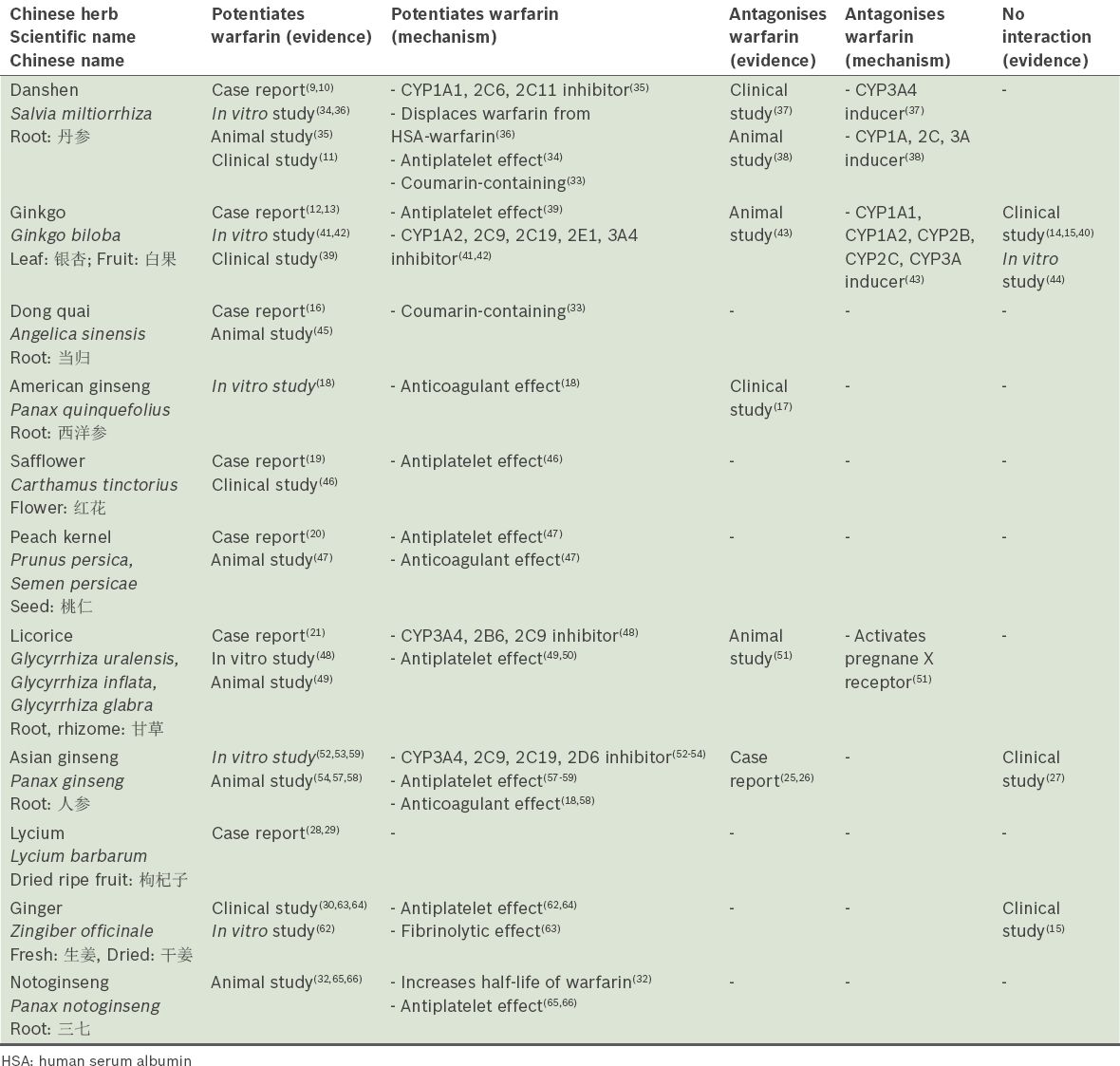

Table I

Summary of existing evidence of the interaction between warfarin and Chinese herbal medicines.

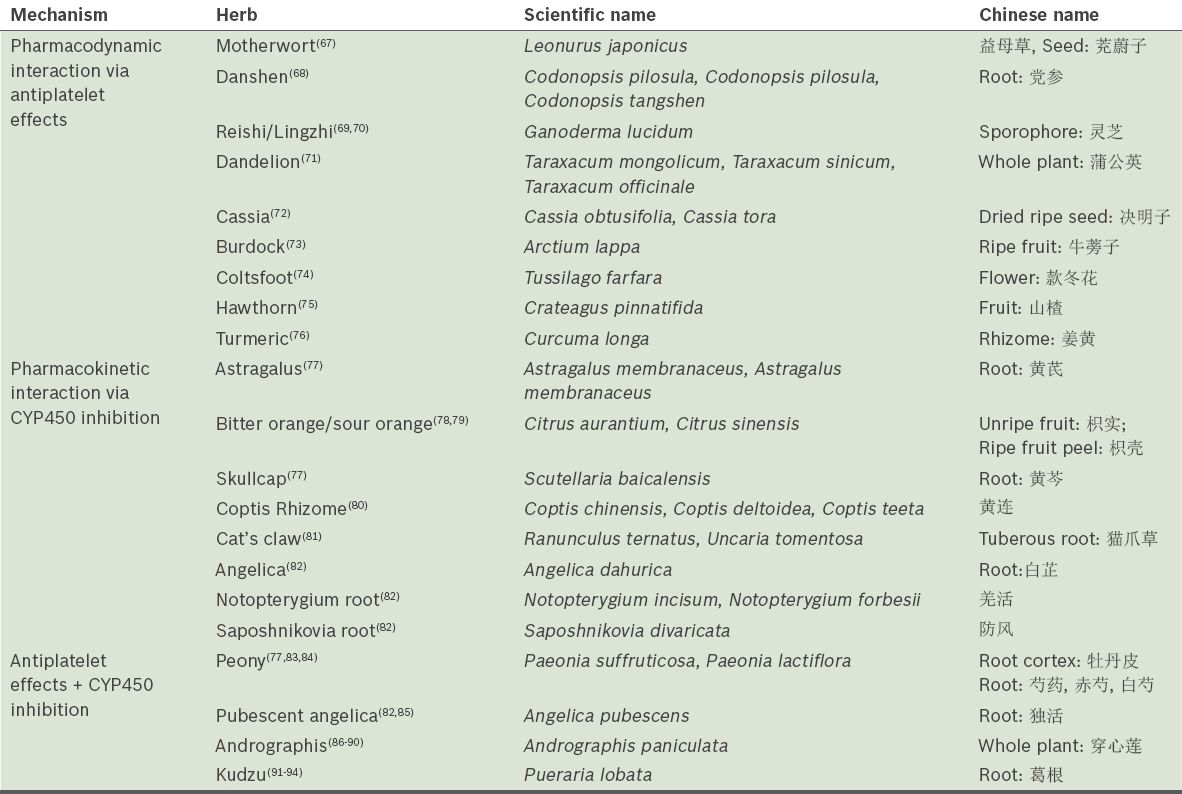

Table II

Proposed mechanism of interaction between warfarin and other Chinese herbal medicines.

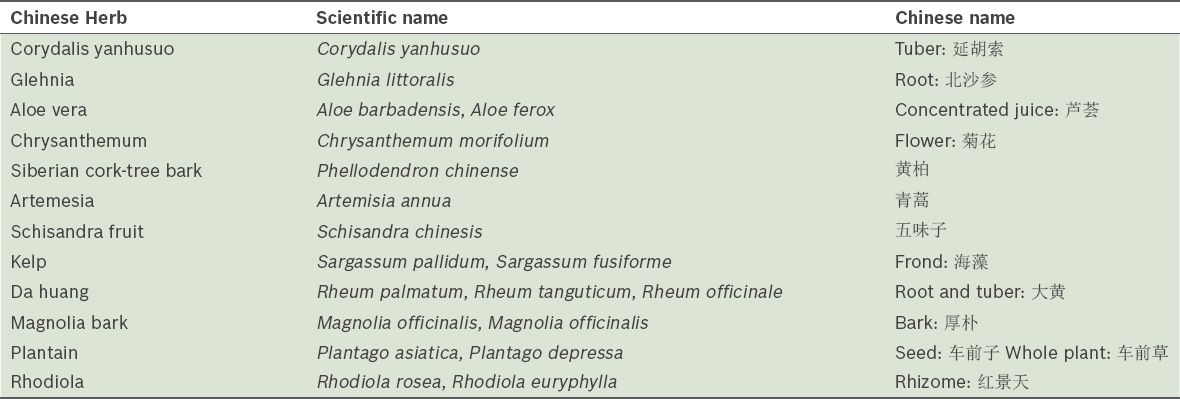

Table III

Chinese herbs (scientific and Chinese names) with no evidence of interaction with warfarin.

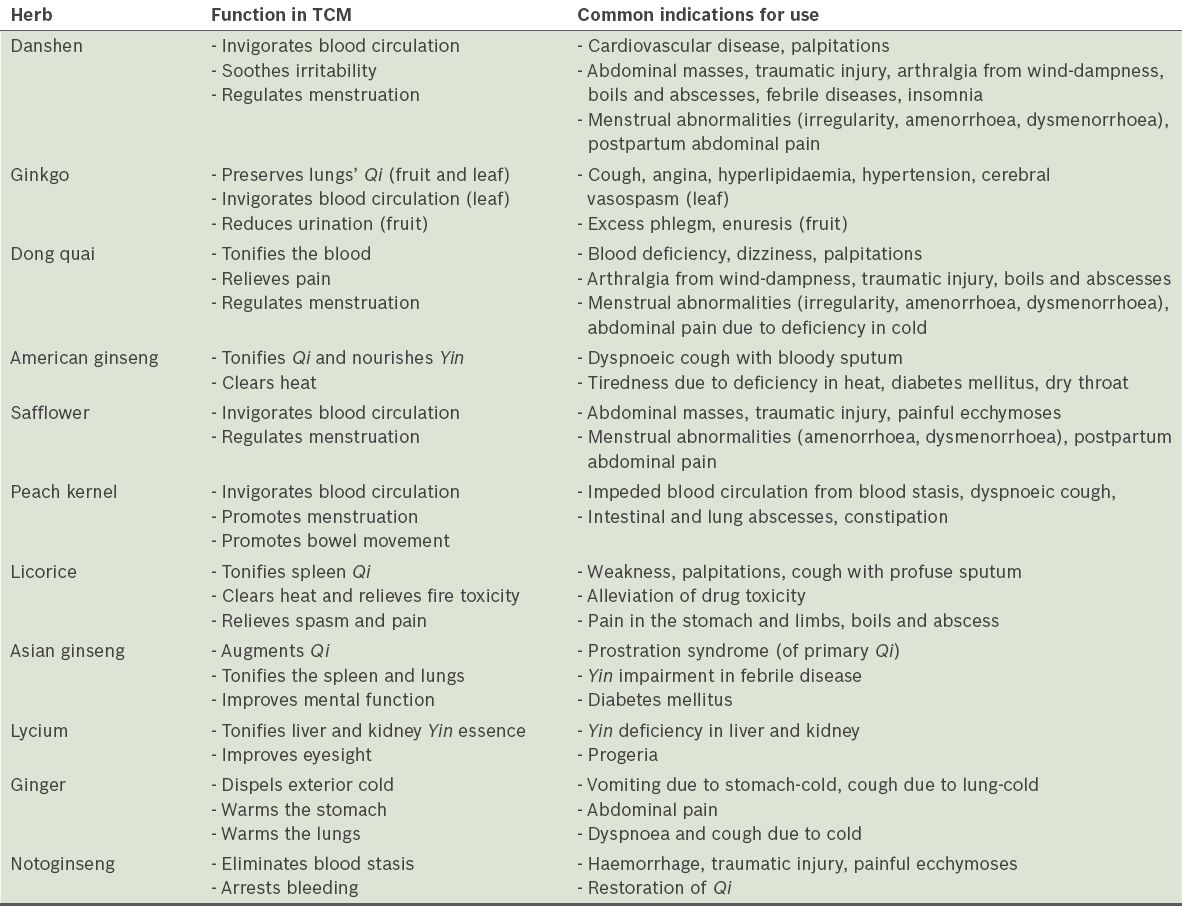

Table IV

Common traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) uses of the Chinese herbs with the greatest evidence of interaction with warfarin.

DISCUSSION

This review has evaluated the current published evidence regarding the herb-warfarin interactions of 44 commonly used Chinese herbal products in Singapore. Of these, 11 herbs (danshen, ginkgo, dong quai, American ginseng, safflower, peach kernel, licorice, Asian ginseng, lycium, ginger and notoginseng) were found to have the strongest evidence of potential interaction with warfarin. Expounded below is a discussion of published studies regarding the interactions of the aforementioned herbs as well as the evidence of their interactions with warfarin. Refer to the appendix for further information regarding the proposed mechanism of herb-warfarin interactions.

Danshen 丹参 (Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge.)

Published case reports have pointed to over-anticoagulation associated with concomitant danshen and warfarin use.(9,10) A 62-year-old man developed haemothorax two weeks after daily consumption of a danshen decoction (INR > 8.4). Dechallenge of danshen with reintroduction of warfarin at original dosage returned his INR to therapeutic range.(9) In addition, a controlled clinical trial (n = 40) concluded that concomitant administration of two weeks of danshen with warfarin significantly prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and INR, as compared to those in the control group.(11)

Ginkgo 银杏, 白果 (Ginkgo biloba L.)

Numerous case reports of spontaneous bleeding with warfarin have been published. From 1966 to October 2004, 15 case reports were published describing the temporal association of ginkgo with bleeding.(12) There was a single case report of a 78-year-old patient on warfarin who, following ginkgo consumption, developed intracerebral bleeding, which stopped with the discontinuation of ginkgo.(13)

However, clinical trials conducted have not substantiated these reports. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-crossover trial (n = 24) of patients who were stable on warfarin concluded that consumption of daily Ginkgo biloba 100 mg for four weeks had no significant influence on warfarin response.(14) Similarly, an open-label crossover study (n = 12) concluded that ginkgo at recommended doses did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of a single 25 mg dose of warfarin in healthy subjects.(15)

Dong quai 当归 (Angelica sinensis [Oliv] Diel)

A case report illustrated a 46-year-old woman on warfarin 5 mg/day who developed two episodes of raised INR of 4.05 and 4.90, related to oral dong quai administration of 565 mg 1–2 times daily. A month after dong quai was discontinued, with warfarin dose maintained, her INR dropped to 2.48.(16)

American ginseng 西洋参 (Panax quinquefolius L.)

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of healthy patients (n = 20) concluded that two weeks of American ginseng 1.0 g twice daily significantly reduced peak INR, peak plasma warfarin and warfarin area under the curve.(17) However, experimental studies have yielded conflicting results. A study by Li et al found that Panax quinquefolius significantly extended activated partial thromboplastin time, PT and thrombin time in human plasma in vitro.(18)

Safflower 红花 (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

A case report depicted bleeding and raised INR associated with safflower use.(33) A 74-year-old man on warfarin 1.25 mg/day with therapeutic INR developed haematuria after 14 days of consumption of safflower 20 g (INR 5.31). When he was subsequently restarted on the same dose of warfarin without safflower use, his INR dropped to 1.64–2.57. However, it was highlighted that at 20 g, the patient had exceeded the recommended safflower daily dosage of 10 g.(19)

Peach kernel 桃仁 (Prunus persica [L.] Batsch, Semen persicae)

A case report illustrated a 54-year-old woman on stable warfarin (INR 2.0–2.5) who experienced an isolated episode of INR at 5.5, related to daily consumption of peach kernel. Dechallenge of peach kernel with original warfarin dose resulted in normalisation of INR to 2.1.(20)

Licorice 甘草 (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., Glycyrrhiza inflata Bat., Glycyrrhiza glabra L.)

A case report described an 80-year-old woman on stable warfarin who developed two episodes of melaena (INR 9.1 and 5.5) associated with ingestion of a pound of black licorice.(21) After dechallenge of licorice, her INR normalised to 1.2 two weeks later.

Asian ginseng 人参 (Panax ginseng)

The effect of ginseng on warfarin has not been established due to abundant conflicting results. Ginseng has been associated with a few episodes of spontaneous bleeding,(22-24) but have also been associated with reports of subtherapeutic INR and thrombosis in patients previously stable on warfarin.(25,26)

The effect of ginseng on warfarin has not been replicated in clinical trials. A randomised, open-label, controlled study of newly diagnosed ischaemic stroke patients (n = 35) found that two weeks of concomitant use of Panax ginseng extract 1.5 g with warfarin did not significantly affect peak values, INR and PT area under the curve, thus concluding that Panax ginseng did not influence the pharmacological action of warfarin.(27)

Lycium 枸杞子 (Lycium barbarum L.)

There has been evidence of potentiation of warfarin linked to the consumption of this Chinese herb, as published in case reports of raised INR and bleeding associated with concomitant use of warfarin and lycium. A 71-year-old woman developed epistaxis, ecchymosis and haematochezia (INR of indeterminate level)(28) and an 80-year-old woman on warfarin (weekly dosage 15.5–16.5 mg) with therapeutic INR developed two episodes of raised INR (4.97 and 3.86) associated with the consumption of concentrated herbal tea containing Lycium barbarum (estimated dosage 20–40 g/day) for 1–2 days prior to blood-taking.(29) Avoidance of the herbal tea returned INR to therapeutic range.

Ginger 生姜, 干姜 (Zingiber officinale Rosc.)

A prospective longitudinal study of patients on warfarin (n = 171) found that ginger was independently associated with increased risk of self-reported bleeding.(30) Although studies on interaction between ginger and warfarin were not found, a case report illustrated an over-anticoagulatory effect of ginger on phenprocoumon, a coumarin derivative.(31) A 76-year-old woman on long-term phenprocoumon with stable INR within therapeutic range developed epistaxis (INR > 10), related to several weeks of regular ginger intake in the form of dried ginger and tea from ginger powder. Discontinuation of ginger and resumption of phenprocoumon at previous dose returned INR to therapeutic range. The Naranjo probability scale scored ginger as a probable cause of the over-anticoagulation.

Notoginseng 三七 (Panax notoginseng [Burk.])

Clinical studies or case reports on interaction between Notoginseng and warfarin were not located. However, experimental studies conducted in rats found that administration of notoginseng 20 mg/kg/day for five weeks increased the Tmax, half-life and area under the curve of warfarin.(32)

It is acknowledged that this review has some limitations. Firstly, the use of only two databases may have limited the papers retrieved; however, both selected databases are established ones, with PubMed displaying over 25,000 journals and Wanfang, about 200 selected Chinese medical journals. Secondly, the list of 40 potential herb-warfarin interactions is not exhaustive. Also, data processing was complicated by the exclusion of scientific names of herbs in some published papers; thus, discretion had to be exercised in such cases. Another limitation stems from the common prescription of Chinese herbs in formulas, which renders this combinatory effect of multiple Chinese herbs on warfarin difficult to address due to the customisation of prescribed formulas, and thus, this has not been explored in our paper. Notably, there was a paucity of high-level evidence (such as meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials) in this area of research. The deliberate inclusion of in vitro studies, animal studies and case reports in this review article was made in an attempt to elucidate the possible interactions with warfarin in vivo. Finally, conflicting results of herb-warfarin interaction further complicated the review of data. For instance, in the case of danshen, while some case reports, animal studies and in vitro studies have suggested a possible potentiation effect, other clinical studies and animal studies have suggested a possible antagonistic effect between the two instead. As such, we recommend that more high-quality studies (i.e. randomised controlled trials) be conducted and that more case reports be documented regarding herb-warfarin interaction.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE

This review article has identified the possible effects of 44 commonly consumed TCM herbs and supplements on warfarin, and provided recommendations with regard to concomitant ingestion with warfarin. We strongly encourage the cooperation of both Western doctors and Chinese physicians in ensuring safety in patients on warfarin. Western doctors are advised to regularly screen for TCM use, especially in patients with indications as listed in

Many of the interactions of herbs with warfarin are extrapolated from experimental studies; the in vivo effects on humans, however, remain to be found. We also acknowledge that many other herb-warfarin interactions likely go unrecognised by unsuspecting practitioners. As such, we advise that practitioners be cognisant of the entity of herb-warfarin interactions and maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with poor INR control. In view of the documented reports and studies highlighting the risk of over- or under-anticoagulation of the 11 herbs (i.e. danshen, ginkgo, dong quai, American ginseng, safflower, peach kernel, licorice, Asian ginseng, lycium, ginger and notoginseng) with warfarin, we opine that it would only be prudent to exercise caution in cases of concomitant use of these herbs with warfarin.

Despite their vast differences, both Western and Chinese medicines are employed with the similar goal of optimising patient outcomes. It is our belief that in the near future, with the aid of further studies dedicated to the advancement of knowledge in this area, close cooperation between Western and Chinese physicians will allow for Chinese herbs and Western medicines to be concomitantly prescribed for synergistic effects.

Supplementary Material

SMJ-56-18-appendix.pdf

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Associate Professor Lau Tang Ching, Senior Consultant, National University Hospital, Singapore, and Physician He Qiu Ling, Senior Physician, Eu Yan Sang Integrative Health Pte Ltd, Singapore, for their comments and suggestions, and Miss Eva Shen for her administrative support.