Abstract

Advance Care Planning (ACP) is a process of discussion of healthcare decisions with regard to a patient’s future health and personal care, should they become unable to make or communicate their own decisions in the future. ACP can be as simple as a chat about the patient’s end-of-life wishes with their trusted loved ones, and may involve their doctors, organisations and trained facilitators. The process can be documented with available online resources, such as structured tools. Family physicians, with whom patients share unique therapeutic relationships, are in the best position to introduce and start the ACP conversation with their patients.

Mr Cheok entered your consultation room in an unusually low mood. Before you could greet him, he lamented, “Doctor, I do not want to carry on with life if I need tubes everywhere in my body… not that way.” He went on to relate how his elder brother had suffered a stroke and had been hooked onto machines in the intensive care unit for the past two weeks. He looked to you for advice on signing an Advance Medical Directive or making a will to prevent himself from being in the same situation as his brother and unable to make his own choices.

HOW COMMON IS THIS IN MY PRACTICE?

What is Advance Care Planning?

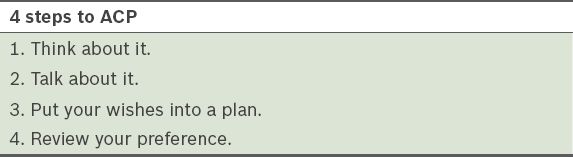

Advance Care Planning (ACP) is a process of discussion of healthcare decisions for a patient’s future health and personal care (

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

ACP is an important discussion that is currently not widely adopted by both clinicians and the public. The Mental Capacity Act, which came into effect in March 2010, introduced important practice implications for all clinicians with regard to accurately assessing the mental capacity, identifying the correct proxy decision-maker and acting in the best interest of the patient, including any previously expressed wishes or preferences in the consideration of patient care.(2)

Foo et al concluded that nearly all their surveyed clinicians in Singapore will involve the patient’s immediate family in discussions of care options for patients who lose decision-making capacity. However, in the making of healthcare plans, they found that the family’s preferences may sometimes be regarded higher than the patient’s previously expressed wishes.(3,4) This suggests that ACP had yet to take root in our local community at the time of the survey. Ng et al listed some common barriers in exploring ACP, including it being culturally taboo to talk about end-of-life issues and a fear of destroying hope, especially for the older generations of Singaporeans.(5)

Who needs Advance Care Planning?

ACP is for any patient who is ready. It is important because it helps patients to start the conversation and communicate their future healthcare preferences to their loved ones, next-of-kin and their attending healthcare professionals. Family physicians, with whom patients share a unique therapeutic relationship, are in the best position to introduce ACP and start the discussion with their patients.

Initiating the ACP conversation gives permission for patients to talk about end-of-life issues, and through the process, explore their options regarding healthcare. Their wishes and preferences expressed through ACP, which are preferably documented, can then be noted by their loved ones and shared with healthcare providers or teams.

How will patients know their future health states or options to make the best decisions for themselves?

ACP is meant to be an ongoing communication process that does not end after one session. The conversations can and should continue within the family and with loved ones, ACP facilitators and health professionals. These discussions can keep the patient abreast of his or her health situation and help the patient reflect, plan and make decisions for future healthcare needs.

Why must Advance Care Planning be documented?

As mentioned, ACP is a process that happens before the patient loses the capacity to make specific healthcare decisions by themselves. As an informal discussion with their loved ones may not be documented, and it is not possible to know when anyone could lose their mental capacity, documented care preferences can relieve the patient’s family of the added stress of remembering the details of these conversations in situations that can be challenging and stressful. It is preferable to have the patient’s preferences documented, as this will guide the family and clinical team in making care and treatment decisions in the best interest of the patient.

Who can be appointed as the patient’s substitute decision-maker?

The substitute decision-maker must be at least 21 years old, able to respect and honour the patient’s preferences under stressful conditions, and must have expressly accepted the role. Patients may choose a relative, best friend or anyone they think will act in their best interests when they are no longer able to do so. It will be very helpful, and it is strongly encouraged, for the appointed and willing substitute decision-maker to participate actively in the process of doing up the ACP. The substitute decision-maker can only make decisions on the patient’s behalf when the patient lacks the capacity for decision-making. If the patient still has the capacity, healthcare professionals will obtain consent from the patient.

There are two categories of substitute decision-makers:

-

Informally appointed substitute decision-maker.

One or more person(s) can be chosen during the ACP process and the choice will be noted in the patient’s medical records. As a matter of good practice, healthcare professionals will consult the substitute decision-maker when the patient has lost decision-making capacity and there is a decision to be made, even though there is no legal requirement for them to do so.

-

Formally appointed substitute decision-maker (donee).

One or more person(s) (donee[s]) can be formally appointed by the patient (donor), using a Personal Welfare Lasting Power of Attorney, to make healthcare decisions on behalf of the patient if the capacity to do so is lost in the future. Donees must always make decisions in the best interest of the donor, and these interests are not restricted to healthcare considerations. Healthcare professionals must, by law, consult the donee on healthcare decisions (when the patient has lost decision-making capacity), except in emergency and time-sensitive circumstances.

Advance Care Planning in Singapore

Living Matters is the local ACP framework in Singapore. It is adapted from the Respecting Choices model based in the United States.(6) There are also resources online to help clinicians, individuals or their loved ones begin the ACP process and explore the option of documenting their care preferences. The attending family physician can help to document any care preferences and decisions that their patients may express and share these with the family or other clinicians helping in the medical care of the patient, if and when the need arises.

For patients with more complex conditions, ACP discussions may need to be facilitated by a trained healthcare professional. These facilitators are currently available in most Singapore public hospitals. ACP is not a legal document; therefore, there is no need for the presence of lawyers for its discussion or documentation.

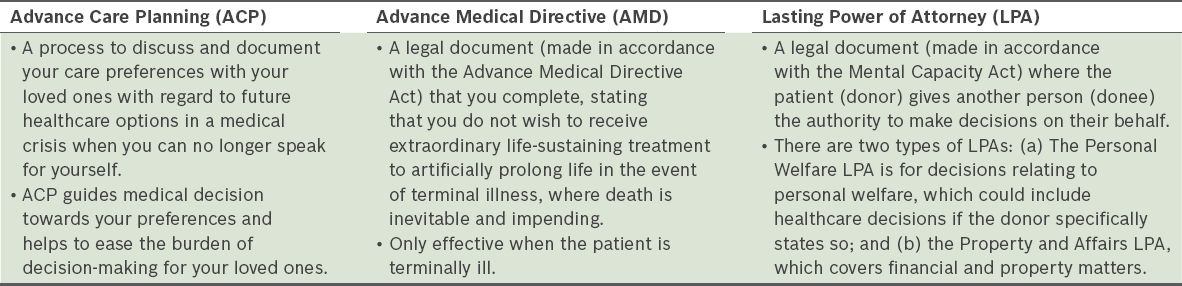

ACP is often confused with Advance Medical Directive or the writing of a will, although these components may be discussed as part of the ACP conversation.

Table II

Differences between Advance Care Planning, Advance Medical Directive and Lasting Power of Attorney (adapted from Living Matters).(1)

Will and testament

A will and testament is a legal instrument made by a person (testator) that states how the testator’s property should be managed and distributed after the testator’s death. A will takes effect only after the testator’s death and not when they are still alive but not able to make their own decisions.

You empathetically allowed Mr Cheok to share more about his brother before printing out the Voice Your Choice brochure from the Living Matters website. You briefly went through the differences between Advance Care Planning (ACP) and Advance Medical Directive, and how he can find out more about ACP from the Living Matters website. You also provided a short memo for Mr Cheok’s respiratory specialist in the hospital for an appointment with a trained ACP facilitator.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Family physicians, with whom patients share unique therapeutic relationships, are in the best position to introduce and start the conversation regarding ACP.

-

The ACP conversation gives permission for patients to talk about end-of-life issues, and through the process, explore their healthcare options.

-

The clinician must be culturally sensitive when trying to identify patients ready to discuss ACP, as some may still consider it taboo to talk about end-of-life issues and possess a fear of having hope destroyed, especially for the older generations of Singaporeans.

-

Living Matters is the local ACP framework in Singapore, with helpful resources online about ACP and the options of documenting patients’ care preferences.

USEFUL LINKS

The Living Matters ACP framework:

More about ACP:

More about lasting power of attorney:

More about advance medical directives:

More about making a will: