Abstract

INTRODUCTION

There is an increasing reliance on informal caregivers to continue the care of patients after discharge. This is a huge responsibility for caregivers and some may feel unprepared for the role. Without adequate support and understanding regarding their needs, patient care may be impeded. This study aimed to identify the needs valued by caregivers and if there was agreement between acute care nurses and caregivers in the perception of whether caregiver needs were being met.

METHODS

We conducted face-to-face interviews with 100 pairs of acute care nurses and caregivers. Participants were recruited from inpatient wards through convenience sampling. Questionnaires included demographic data of nurses and caregivers, patients’ activities of daily living, and perception of caregiver needs being met in six domains of care. Independent t-test was used to compare mean values in each domain, and intraclass correlation coefficient was used to compare agreement in perception.

RESULTS

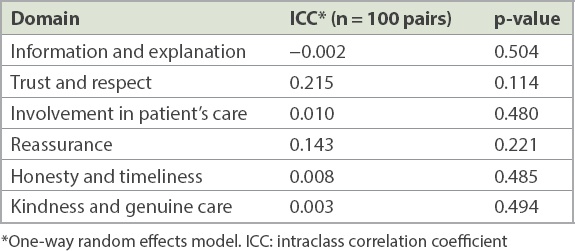

Caregivers valued reassurance the most. Three domains of care needs showed significant differences in perception of caregiver needs being met: reassurance (p = 0.002), honesty and timeliness (p = 0.008), and kindness and genuine care (p = 0.026). There was poor agreement in all six domains of caregiver needs being met between nurses and caregivers.

CONCLUSION

Although caregivers valued reassurance the most, there was poor agreement between acute care nurses and caregivers in the perception of caregiver needs being met. Hence, more attention should be paid to the caregiver’s needs. Further studies can examine reasons for unmet caregiver needs and interventions to improve support for them.

INTRODUCTION

As Singapore faces a rapidly ageing society and an increasing burden of chronic diseases,(1) the reliance on family caregivers to continue the care of our patients after hospital discharge will increase. This encourages healthy family caregivers to take on informal caregiving roles and alleviate the burden on an increasingly overwhelmed healthcare system. Over the years, informal caregivers have become ‘lay nurses’, performing complex tasks such as medication management, injections, complex wound care and tube feeding, among others.(2) Caregivers also serve as care navigators, managing patients’ multiple appointments, arranging transportation for appointments and coordinating various community services. With this huge responsibility, some caregivers may feel unprepared, have inadequate knowledge and receive little guidance from healthcare providers.(3)

Often, healthcare providers fail to identify caregiver needs or acknowledge the important role that they play. Without adequate preparation and support, caregivers may be unfamiliar with the type of care they must provide or the amount of care that is needed by the patient after hospital discharge.(4) Caregivers often switch from being totally dependent on nurses while the patient is in the hospital to total self-reliance at home. They are often overwhelmed by the information and the complexity of the tasks they are expected to perform, which inadvertently leads to caregiver stress.

Providing quality care for the patient often requires an understanding of caregiver needs; in turn, meeting those needs is essential to the effectiveness of care delivery and patient outcome. Caregivers with unmet needs may be impeded in their ability to function effectively, including in their role as an ongoing support system for the patient,(4) which adversely affects the patients’ own state of physical and mental well-being in the recovery phase,(5,6) resulting in hospital re-admission and earlier institutionalisation.(7)

As understanding caregiver needs is an important component of an effective discharge planning process, it should be done as early as during admission so that optimal interventions can be carried out. It is important to identify the many roles of caregivers, the challenges they face, gaps in knowledge and skills, and the kind of help that would be both useful and acceptable to the caregiver.(8) Nurses are in a unique position to work with families as partners in providing this care. It has been shown that what patients and caregivers value most from healthcare providers is information, explanation, trust and respect.(9) Other needs include honesty, reassurance and timely response to requests.(10,11) Caregivers said they value information that extends beyond clinical information or skills. They also value staff who encourage them to ask questions, request for help or seek clarification, taking time to explain and checking if the caregiver understood the information, as well as the attitude of staff in making the caregiver feel respected and valued.(9) The aim of this study was to identify the caregiver needs that caregivers value and to assess if there was agreement in the perception of caregiver needs being met between our acute care nurses and caregivers.

METHODS

We performed a cross-sectional descriptive study at Singapore General Hospital, one of the largest tertiary care hospitals in Singapore.(12) The study was conducted over a period of 12 months, from May 2015 to June 2016.

A total of 100 pairs of acute care nurses and caregivers were recruited through convenience sampling from all inpatient wards in the hospital. Each pair, consisting of acute care nurse and caregiver, rated the perception of caregiver needs being met for their patient. Inclusion criteria for the nurses were: at least one year of working experience as a registered nurse, and direct care with the patient and caregiver. Included caregivers were unpaid, involved in the patients’ care and/or involved in decision-making on the patients’ behalf. The patient had at least one chronic disease and needed permanent assistance in at least one of their activities of daily living (ADLs) such as bathing, eating, transferring, continence, dressing or toileting. Exclusion criteria were caregivers who were paid for their service or whose patients were being discharged to a long-term-care nursing facility.

All ward nurses were informed of this study through roll calls and emails. Ward nurses called the principal investigator or study members whenever there was an eligible patient or caregiver. The principal investigator or study members would then approach the caregiver and the nurse to explain the purpose of the study and obtain their written consent. The interview took 20 minutes to complete; it was held at the patient’s bedside for the caregiver and at the end of the shift for the nurse.

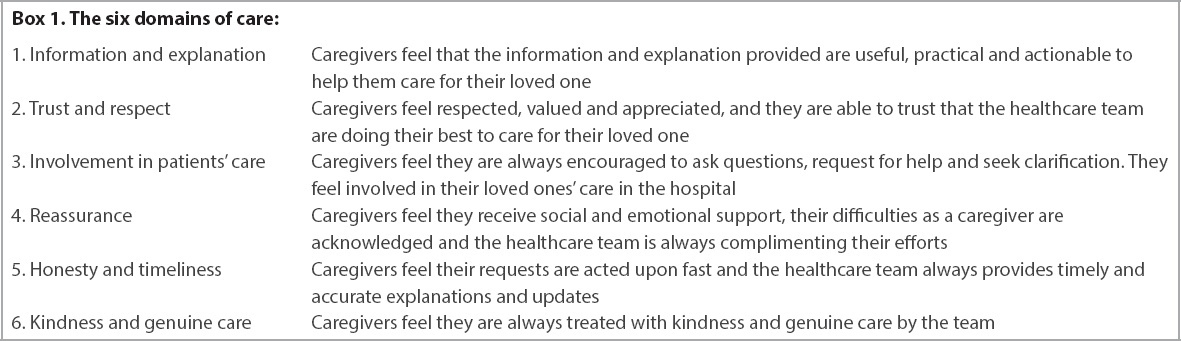

The questionnaire was developed by the study team. The caregiver’s questionnaire included sociodemographic information, the patient’s ADL status and perceived caregiver needs being met in the six domains of care: (1) information and explanation; (2) trust and respect; (3) involvement in patients’ care; (4) reassurance; (5) honesty and timeliness; (6) and kindness and genuine care (

Box 1

The six domains of care:

Each question was rated using a Likert scale of 1 to 5 (1 = needs are not met at all, 2 = needs are occasionally met, 3 = neutral, 4 = needs are frequently met, 5 = needs are fully met). We considered ratings of 4 and 5 on the Likert scale as representing that caregivers’ needs were being adequately met. Caregivers also rated the top three care needs that were important to them.

The nurse’s questionnaire consisted of 29 questions, while the caregiver’s questionnaire consisted of 31 questions (Appendices 1 & 2). Caregivers had additional questions on: other responsibilities such as holding a job or taking care of young children; additional help received at home such as a foreign domestic helper; and duration of caregiving. This information is important and can have an impact on their perception of needs being met. Caregivers also self-rated the screening version of the Zarit Burden Interview to measure their level of burden, in which a score > 8 indicates high burden. The validated four-item Zarit Burden Interview has been shown to be practical to use and easy to administer.(13)

Statistical analysis was computed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data was used to present the demographic characteristics of the sample as well as outcome measures for the caregiver and nurse groups. Parametric independent t-test was used to compare perceived caregiver needs between nurses and caregivers, while intraclass correlation coefficient was used to compare agreement in the perception of caregiver needs being met between nurses and caregivers.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref 2015/2557) before commencement of the study. All participants were provided with an information sheet that explained the study and given the opportunity to ask questions. Written consent was taken and each questionnaire was coded to ensure anonymity, with all identifiable data being removed. Voluntary participation, confidentiality and the right to withdraw were also explained. Participants were assured that all information was limited to the investigators only. Patients who were cognitively normal were informed that their caregivers were participating in the study.

RESULTS

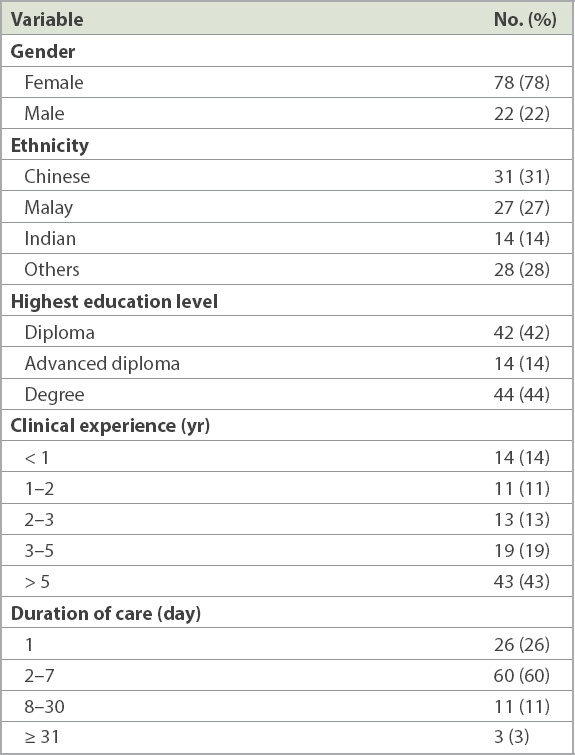

A total of 100 nurses and 100 corresponding caregivers completed the survey. The majority of the nurses interviewed were female (78%). Their ethnic distribution was Chinese (31%), Malay (27%), Indian (14%) and others (28%). More than half had received higher education and were experienced nurses. The duration they spent with the patient and caregivers ranged from one to seven days (86%). Only three nurses reported providing care for 31 days or more (3%) (

Table I

Demographic profile of nurses interviewed.

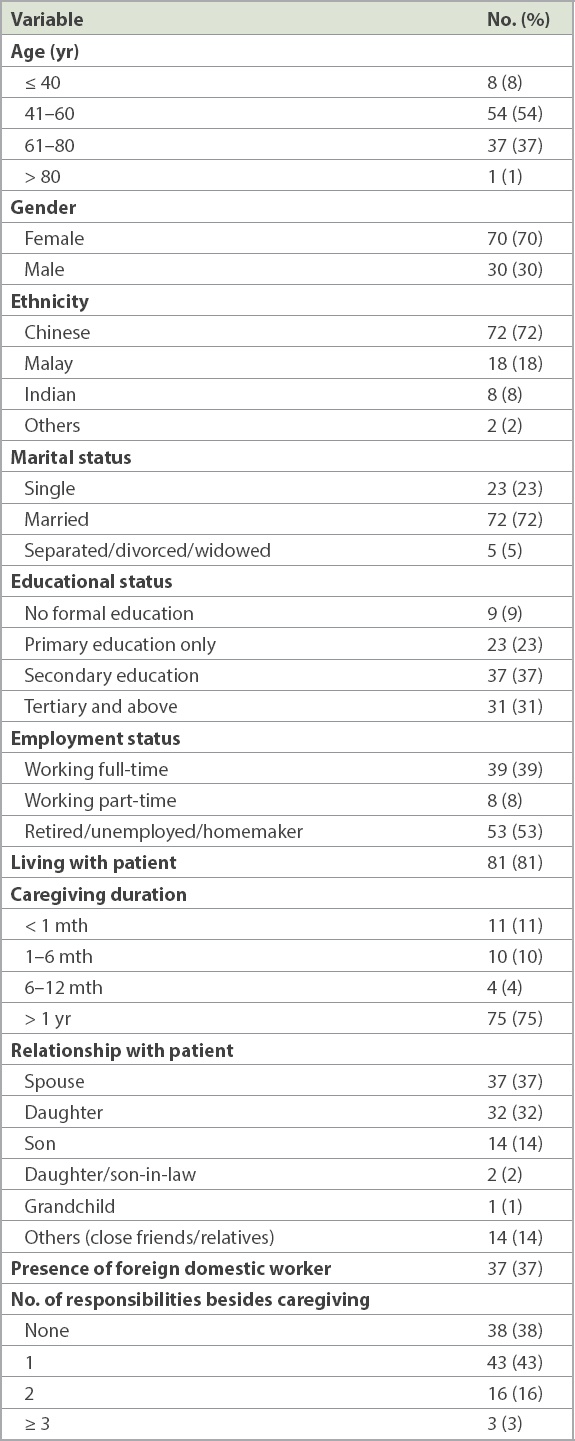

The majority of the caregivers were aged > 40 years (92%) and of the female gender (70%), with an ethnic distribution of Chinese (72%), Malay (18%), Indian (8%) and others (2%). Most were married and had secondary education or less. Almost half of the caregivers were still working full-time or part-time (47%). A high proportion of caregivers were living together with the patient (81%) and had been performing caregiving duties for more than one year (75%). Caregivers were either spouses (37%) or daughters (32%), and the majority had only one or no other responsibilities besides caregiving. Only 37% reported having a domestic worker to help with the caregiving (

Table II

Demographic profile of caregivers interviewed.

The mean age of the patients was 72 years and they had an average of three chronic comorbidities. Regarding the need for permanent assistance in ADLs, 83% of the patients required this in 4–6 ADLs, 16% in 2–4 ADLs and only 1% in one ADL. Hence, the caregivers surveyed were looking after a population with high care needs.

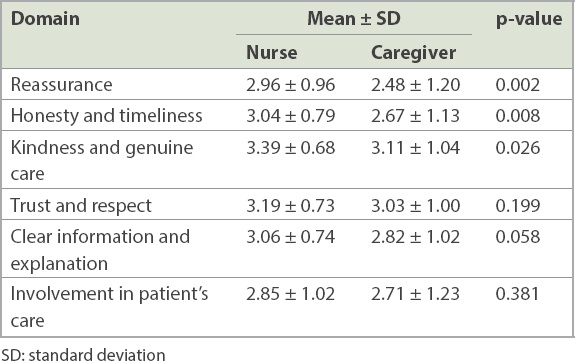

An independent t-test showed three domains with significant difference in the perception of caregiver needs being met between acute care nurses and caregivers, namely: reassurance (nurses 2.96 ± 0.96, caregivers 2.48 ± 1.20, p = 0.002); honesty and timeliness (nurses 3.04 ± 0.79, caregivers 2.67 ± 1.13, p = 0.008); and kindness and genuine care (nurses 3.39 ± 0.68, caregivers 3.11 ± 1.04, p = 0.026) (

Table III

Analysis of the six domains of care needs.

Although there are no significant differences in these domains, it is noted that caregivers rated low, especially on clear information and explanation as well as involvement in patients’ care (

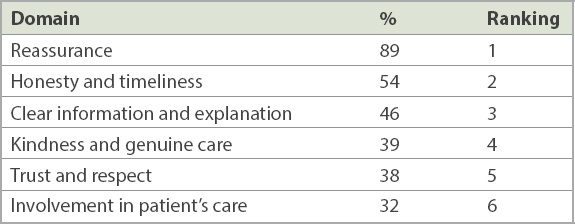

We also asked the caregivers to rank the top three domains of care needs that were most important to them, out of the six domains (

Table IV

Ranking of caregiver’s most important care needs.

Table V

Correlation between nurses and caregivers’ perception of caregiver needs being met.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, caregivers rated reassurance as their most important care need although it was not met. In a busy healthcare setting, caregivers may be ignored but are actually valuable members of the care team. Healthcare providers should engage them with a view to boosting their confidence in providing care to the patient during and after hospital discharge.(3) Caregivers value social and emotional support from the healthcare team and an acknowledgement of their challenges in caregiving. Compassion, respect and empathy could add value to the care they receive.

While more in-depth analysis is needed to evaluate the factors that influence the meeting of caregiver needs, nurses can be more mindful and compassionate in their daily practice by recognising the caregiver’s efforts and providing continuous emotional and social support even after hospital discharge. These findings also provide a basis for transitional care services, such as discharge planning and home health care services,(14-17) to meet their needs and reduce caregiver burden.

Comprehensive discharge planning includes a well-structured nursing assessment of caregiver needs or caregiver burden. These assessments would be helpful in identifying areas that require more attention or early intervention to support our caregivers. Targeted interventions can strengthen the caregivers’ competence and reduce harm to the patient under their care.(3) Caregivers who are well supported and confident in delivering care at home often have better patient outcomes and are able to continue in this role.

Our study was not without limitations. The caregiver interviews could either be done one day after admission or after a few weeks. Therefore, caregivers’ perceptions of needs being met may have varied due to the duration of training and support they received in the ward. Nevertheless, the acute care nurses answered the questions at the same time, hence allowing comparisons to be made. For future studies, the timing of the assessments should be standardised, such as within 24–48 hours of admission. Second, participants were selected through convenience sampling even though random selection would increase the generalisability of our findings. Third, the authors noted that the duration of caregiving may affect perceptions of needs met; for example, the longer the caregiving duration, the more familiar the nurses and the caregiver are with each other, which can affect their perceptions. However, we did not analyse the data by duration of caregiving, because more than 75% of the caregivers had been providing care for more than one year, while 86% of nurses had cared for the patients for a short duration of less than one week. Therefore, there were small numbers in some of the categories, making subgroup analysis inaccurate. Moreover, agreement was already poor and further subgroup analyses were unlikely to change the results. Finally, the six domains of care developed by the authors could have been evaluated in a more rigorous manner using formal tests of reliability.

In conclusion, this study provided valuable insights into the needs that caregivers valued most. The poor agreement in the perception of caregiver needs being met highlights that more attention to caregiver needs is required to ensure that they are being met. Further studies can look into reasons for unmet caregiver needs and create opportunities to further enhance our support for caregivers.