INTRODUCTION

Computed tomography (CT) is a useful tool for emergency cases because it facilitates an accurate and reproducible diagnosis. Emergency cases have various causes, and CT helps to identify characteristics such as abnormal gas in the abdomen and pelvis. Although radiography can detect large amounts of abnormal gas, it cannot evaluate the distribution and amount of the gas in detail (

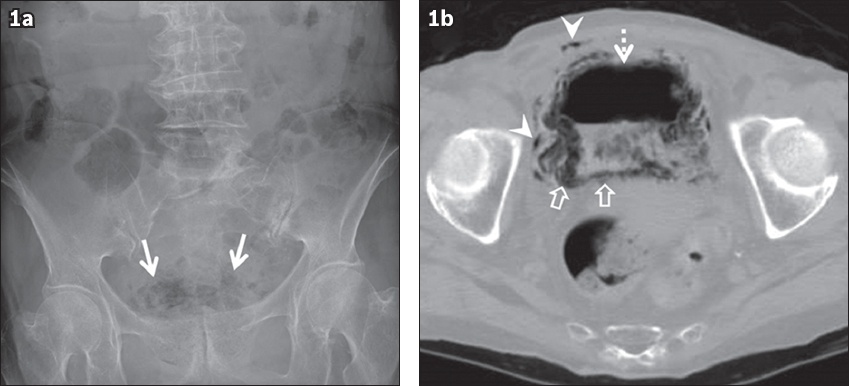

Fig. 1

Emphysematous cystitis in an 84-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus who presented with high fever. (a) Abdominal radiograph shows abnormal gas in the pelvis (arrows); however, it is difficult to evaluate the distribution of the gas. (b) Unenhanced CT image shows the distended urinary bladder with diffuse collection of gas within the bladder wall (open arrows). Intraluminal (dotted arrow) and extraluminal (arrowheads) gas is also observed.

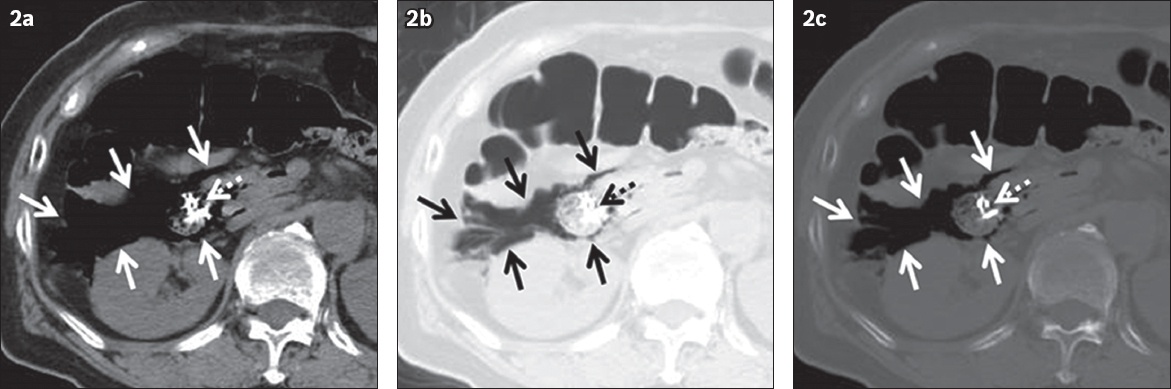

Fig. 2

Pneumoretroperitoneum in a 62-year-old woman who complained of abdominal pain. The pneumoperitoneum was caused by penetration of the second portion of the duodenum during endoscopic mucosal resection for early cancer. Unenhanced CT images – (a) soft tissue window setting (window level/window width, 50/350 HU); (b) lung window setting (−600/1,500 HU); and (c) bone window setting (300/2,000 HU) – show air attenuation areas surrounding the duodenum through retroperitoneal space, suggesting pneumoretroperitoneum (arrows). Abnormal gas can be more easily detected in lung or bone window settings compared to the soft tissue window setting. Dotted arrows indicate metallic clips in the duodenum.

GAS IN VESSELS

Portal venous and mesenteric venous gas are clinically important, because they are commonly caused by serious and potentially fatal conditions including bowel ischaemia, bowel obstruction, bowel perforation and sepsis.(1,5) However, several non-life-threatening causes have also been reported.(1)

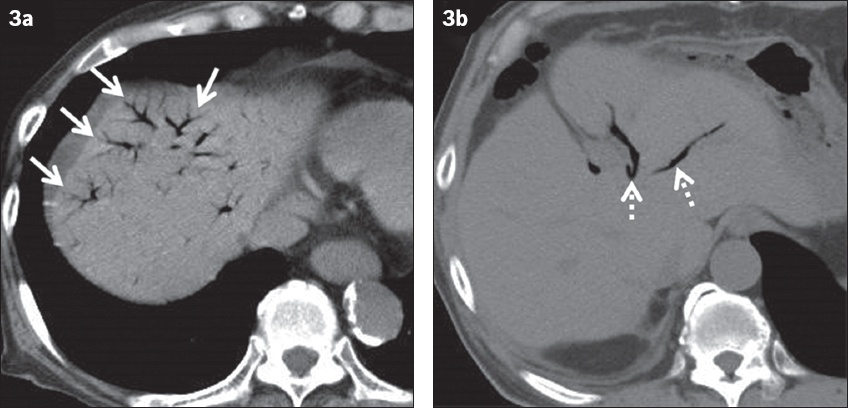

Portal venous gas appears as areas of tubular or branched air attenuation in the portal vein and its branches on CT (

Fig. 3

(a) Portal venous gas in a 91-year-old man caused by non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia presenting as acute abdominal pain. Unenhanced CT image shows areas of branched air attenuation in the periphery of the liver, suggesting portal venous gas (arrows). (b) Asymptomatic pneumobilia in a 71-year-old man with a history of choledochojejunostomy. Unenhanced CT image shows an area of tubular air attenuation located centrally in the liver, suggesting pneumobilia (dotted arrows). It does not extend to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.

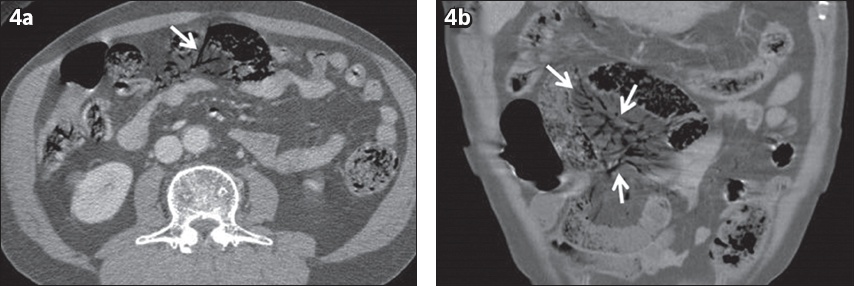

Fig. 4

Mesenteric venous gas in a 71-year-old man caused by non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia presenting as acute abdominal pain. Contrast-enhanced (a) axial and (b) coronal CT images show areas of tubular and branched air attenuation in the mesentery, suggesting mesenteric venous gas (arrows).

Abnormal gas in the aorta can be a sign of a life-threatening condition. However, it is also observed in patients with an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) (

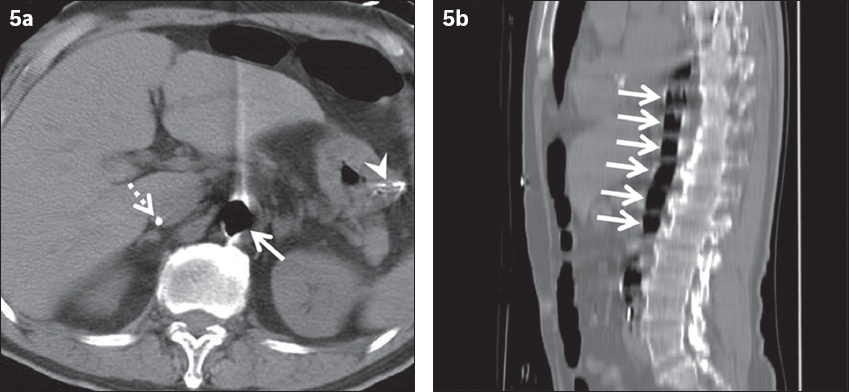

Fig. 5

Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) in a 79-year-old man with multiple organ failure due to acute myocardial infarction presenting as increased pericardial effusion. (a) Unenhanced CT image shows air attenuation in the aorta (arrow) with a Swan-Ganz catheter (dotted arrow) inserted via the femoral vein and a gastric tube (arrowhead). (b) Sagittal CT image shows the IABP as a structure with regular air attenuation in the caudal direction (arrows).

GAS IN THE PERITONEAL OR RETROPERITONEAL CAVITY

Pneumoperitoneum and pneumoretroperitoneum

The presence of gas within the peritoneal cavity (pneumoperitoneum) and the retroperitoneal space (pneumoretroperitoneum) is a crucial imaging finding for gastrointestinal perforation. The direct imaging finding of gastrointestinal perforation is bowel wall discontinuity (

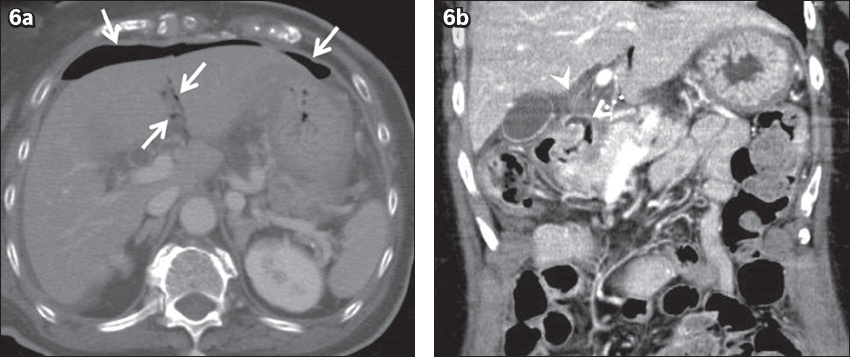

Fig. 6

Pneumoperitoneum in a 71-year-old woman caused by duodenal ulcer at the first portion, presenting as epigastric pain and vomiting. (a) Contrast-enhanced axial CT image shows an area of air attenuation around the liver, suggesting pneumoperitoneum (arrows). (b) Coronal CT image shows duodenal wall discontinuity due to an ulcer at the first portion (dotted arrow), with surrounding fat stranding (arrowhead).

Pneumoperitoneum may be detected owing to reasons other than gastrointestinal perforation, including postoperative state or peritoneal dialysis. However, these typically have no symptoms. Pneumoperitoneum due to open laparotomy decreases over time. However, it can remain for up to two weeks.(4) In patients with peritoneal dialysis, pneumoperitoneum can occur owing to catheter insertion or inappropriate exchange technique for a bag or extension tube, and its incidence rate has been reported to range between 4% and 34%.(7) Therefore, it is important to review the patient’s treatment history to avoid misinterpreting pneumoperitoneum due to postoperative state and peritoneal dialysis as life-threatening pneumoperitoneum. The common causes of pneumoretroperitoneum include duodenal or rectal perforation and extensions from pneumomediastinum. The common causes of pneumoperitoneum and pneumoretroperitoneum are different, but both are potentially serious signs.

Abscess

An abscess may form because of inflammation in the peritoneal or retroperitoneal cavity. Common causes of an intra-abdominal abscess include surgical trauma, anastomotic leaks, perforation of a peptic ulcer, perforated appendicitis or diverticulitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.(8) An abscess is demonstrated as a low-attenuation central necrotic component with an enhancing wall that can be irregular and thick on contrast-enhanced CT. Abnormal gas is often contained in an abscess when gas-producing bacteria are the cause of the abscess (

Fig. 7

Abscess formation in a 22-year-old woman caused by perforated acute appendicitis, presenting as right lower abdominal pain. Contrast-enhanced CT image shows a low-attenuation central necrotic component and gas with enhancing wall in the lower abdomen, suggesting abscess (arrow). An enlarged appendix (dotted arrows) that has an appendicolith (arrowhead) at the tip is seen adjacent to the abscess.

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) is a late complication of necrotising pancreatitis, as defined in the revised Atlanta classification.(9) Peripancreatic fluid collections developing after necrotising pancreatitis have been classified into two categories: (a) acute necrotic collections, defined as non-encapsulated heterogeneous solid and liquid necrotic material within four weeks from necrotising pancreatitis attack; and (b) WOPN, defined as encapsulated heterogeneous solid and liquid necrotic material after four weeks from necrotising pancreatitis attack.(9) Life-threatening complications such as infected WOPN, bleeding or fistulisation into the gastrointestinal tract can occur.(10) On CT, WOPN is demonstrated as a heterogeneous lesion around the pancreas that comprises a non-enhancing area surrounded by a wall (

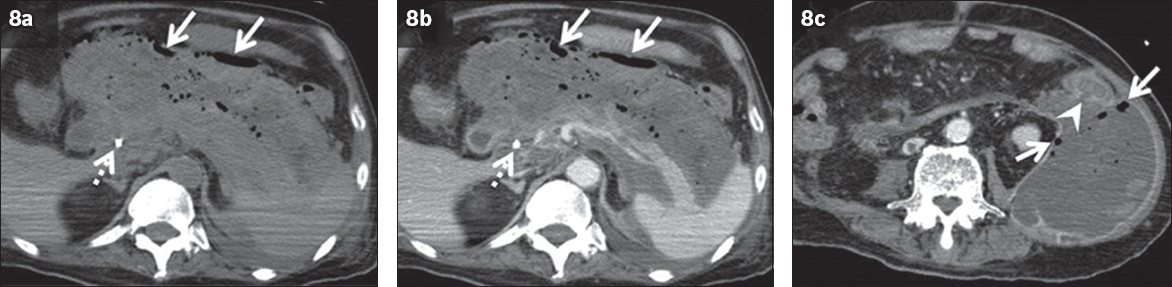

Fig. 8

Fistulisation between walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) and the descending colon in a 74-year-old man 12 weeks after a necrotising pancreatitis attack, presenting as progression of anaemia.(a) Unenhanced; (b) contrast-enhanced; and (c) thin-slice CT images show heterogeneous lesions around the pancreas comprising non-enhancing areas surrounded by a wall, suggesting WOPN. Abnormal gas is observed in the WOPN (arrows), and fistulas between WOPN and the descending colon are clearly visualised on thin-slice image (arrowhead). A biliary stent (dotted arrows) is seen.

Postoperative pancreatic fistula

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is one of the most serious complications after pancreatic resection. It is defined as an abnormal communication between the pancreatic ductal system and another epithelial surface containing pancreas-derived, enzyme-rich fluid.(11) The incidence of POPF ranges between 3% and 45% of pancreatic operations at high-volume centres.(11) For diagnosis, any measurable volume of drain fluid on or after postoperative day 3 with amylase levels > 3 times the upper limit of normal amylase for each specific institution is the necessary threshold, and this condition is defined as biochemical leak (BL) in the latest guidelines.(11) BL is not considered a true pancreatic fistula or an actual complication and implies no deviation in the normal postoperative pathway. Clinically significant POPF is defined as a condition that requires persisting peripancreatic drainage or other treatment in addition to BL.(11) On CT, fluid collection around the pancreatic stump or anastomosis is an indicator of an underlying POPF (

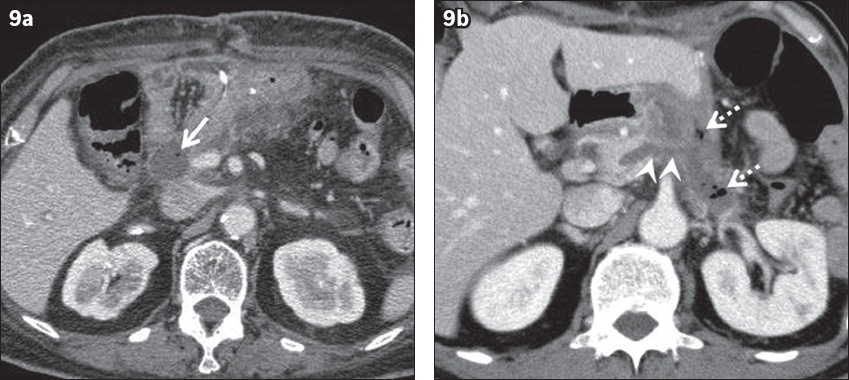

Fig. 9

(a) Biochemical leak (BL) in a 76-year-old woman after subtotal stomach-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy 13 days prior to presentation for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with complaints of fever and vomiting. Contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrates a fluid collection containing abnormal gas (arrow) around the anastomosis site, indicating leak. It was diagnosed as BL because of the high amylase level in the drainage. (b) Grade B postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) in a 67-year-old man after distal pancreatectomy and distal gastrectomy 17 days prior to presentation for PDAC and gastric cancer with a complaint of fever. Contrast-enhanced CT image shows a fluid collection with abnormal gas (dotted arrows) adjacent to the pancreatic stump. Communication between the fluid collection and the pancreatic duct (arrowheads) is clearly demonstrated. Percutaneous drainage was performed and a diagnosis of grade B POPF was established.

GAS IN HOLLOW ORGANS

Pneumatosis intestinalis

Pneumatosis intestinalis is defined as the presence of gas in the bowel wall owing to various causes. It occurs as a primary (idiopathic) form or secondary form in 15% and 85% of cases, respectively.(3) It can be found with portal venous gas and mesenteric venous gas, rendering them related phenomena. Pneumatosis intestinalis is commonly caused by fatal diseases including bowel necrosis, bowel obstruction and bowel perforation. Nevertheless, it has been reported in various pathological conditions including inflammatory bowel disease and chronic pulmonary disease, with corticosteroids or molecular targeted drugs, and trauma that can show better clinical outcomes (so-called benign pneumatosis intestinalis).(3) Three patterns of pneumatosis on CT have been described: a circumferential form in the bowel wall (

Fig. 10

Pneumatosis intestinalis due to bowel necrosis in a 76-year-old man with a complaint of abdominal pain. Contrast-enhanced CT image shows abnormal gas in the small intestinal wall with various patterns, including circumferential (arrows), linear (dotted arrows) and bubble-like (arrowheads) patterns.

Fig. 11

Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis in a 79-year-old man who underwent corticosteroid therapy for lymphoproliferative disease, presenting with abdominal distension and nausea. Contrast-enhanced CT image (lung window) shows multiple areas of circumferential/curvilinear (arrow) and cystic (arrowhead) gas in the small intestinal wall. Abnormal gas in the mesentery is also observed (dotted arrow).

EMPHYSEMATOUS INFECTIONS

Emphysematous infections of the abdomen and pelvis are life-threatening conditions that require aggressive medical and often surgical management. They are rare and typically caused by gas-forming microbes.(2) Underlying diabetes mellitus is a well-known risk factor for emphysematous infections. The clinical outcome will largely depend on whether early diagnosis and treatment are achieved.(2) Thus, it is important to reach the correct diagnosis via imaging.

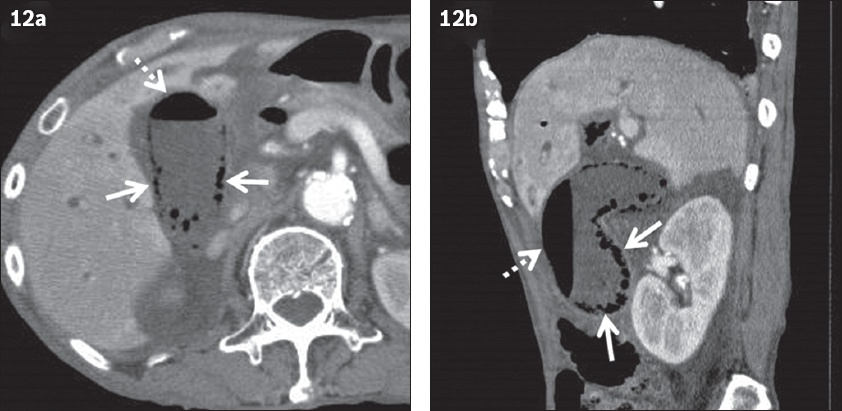

Emphysematous cholecystitis

Emphysematous cholecystitis is a rare form of acute cholecystitis. Vascular compromise of the cystic artery is thought to play a significant role in the evolution of the emphysematous form.(2) The overall mortality rate of patients with emphysematous cholecystitis has been reported as 15%.(2) Emphysematous cholecystitis is characterised by the presence of air within the gallbladder lumen or wall in the absence of abnormal communication between the biliary system and gastrointestinal tract, and CT is the most sensitive and specific imaging modality (

Fig. 12

Emphysematous cholecystitis in an 80-year-old man with complaints of abdominal pain and fever, and a history of diabetes mellitus. Contrast-enhanced (a) axial and (b) sagittal CT images show bubble-like gas in the gallbladder wall (arrows). Intraluminal gas showing air-fluid level (dotted arrows) is also observed. These findings suggest emphysematous cholecystitis.

Emphysematous pyelonephritis

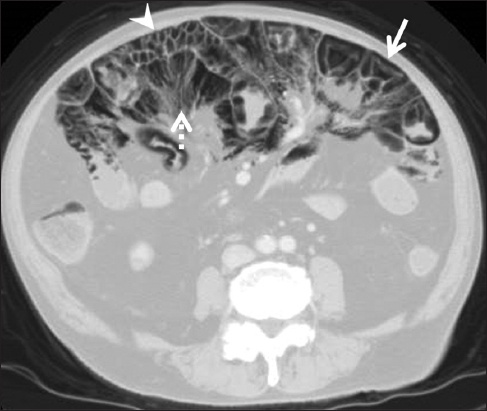

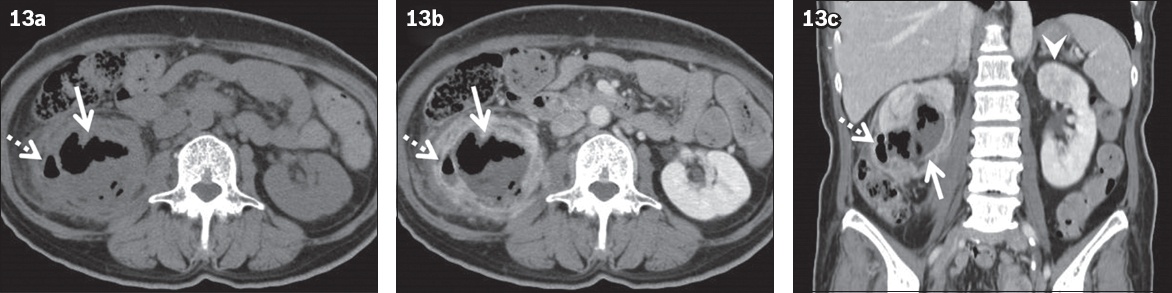

Emphysematous pyelonephritis has been defined as a necrotising infection of the renal parenchyma and perirenal tissue, with abnormal gas in these areas (

Fig. 13

Emphysematous pyelonephritis in a 56-year-old woman with complaints of abdominal pain and fever, and a history of diabetes mellitus. (a) Unenhanced; (b) contrast-enhanced; and (c) coronal CT images show an enlarged, destroyed renal parenchyma with gas and fluid collection in the right kidney (arrows). The gas and fluid collection extends to the pararenal space (dotted arrows). Fat stranding and thickened renal fascia are also observed. Acute focal bacterial nephritis is observed in the left kidney (arrowhead).

Emphysematous cystitis

Emphysematous cystitis is a rare form of complicated infection, with abnormal gas within the bladder wall and lumen. Chronic urinary tract infections, bladder outlet obstruction and a neurogenic bladder are often present.(2) Abdominal radiographs can demonstrate curvilinear or mottled gas in the region of the urinary bladder. However, CT is more useful for detailed evaluation of the distribution and amount of the gas (

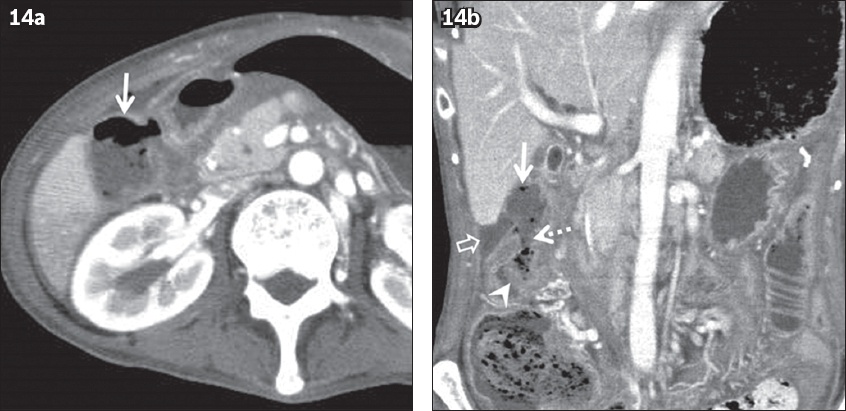

GASTROINTESTINAL FISTULAS

Gastrointestinal fistulas should be considered for possible non-infectious conditions of abnormal gas.(2) The common causes of gastrointestinal fistulas include diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, surgical complications, post-radiation therapy and trauma.(2,14,15) Cholecystoenteric fistula is a rare complication of acute cholecystitis. The most common cholecystoenteric fistula is the cholecystoduodenal fistula, followed by the cholecystocolic fistula.(14) CT can allow direct visualisation of a fistula between the gallbladder and the duodenum or colon (

Fig. 14

Cholecystocolic fistula due to acute cholecystitis in a 63-year-old woman with complaints of right-sided abdominal pain and fever. Contrast-enhanced (a) axial and (b) coronal CT images show abnormal gas in the gallbladder (arrows). A fistula between the gallbladder and the hepatic flexure of the colon is clearly observed on the coronal image (dotted arrow). Local colonic wall thickening (arrowhead) and peritoneal abscess (open arrow) are also observed.

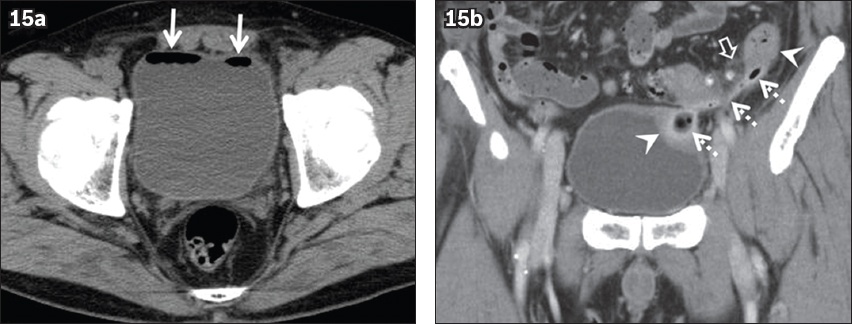

Fig. 15

Colovesical fistula due to sigmoid diverticular disease in a 60-year-old man with recurrent cystitis. (a) Unenhanced CT image shows abnormal gas in the urinary bladder (arrows). (b) Coronal contrast-enhanced CT image clearly shows a fistula between the urinary bladder and sigmoid colon (dotted arrows). Local colonic and bladder wall thickening (arrowheads) and surrounding fat stranding (open arrow) are also observed.

CONCLUSION

CT imaging can play a crucial role in various emergency cases with characteristic abnormal gas in the abdomen and pelvis. Contrast-enhanced CT is useful for improved diagnosis of the site of abnormal gas. Most cases are urgent; therefore, it is important for clinicians to be familiar with their characteristic radiologic features to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

SMJ-63-306.pdf