Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Clinical practice guidelines recommend different blood pressure (BP) goals for chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. Usage of antihypertensive medication and attainment of BP targets in Asian CKD patients remain unclear. This study describes the profile of antihypertensive agents used and BP components in a multiethnic Asian population with stable CKD.

METHODS

Stable CKD outpatients with variability of serum creatinine levels < 20%, taken > 3 months apart, were recruited. Mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured using automated manometers, according to practice guidelines. Serum creatinine was assayed and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) calculated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation. BP and antihypertensive medication profile was examined using univariate analyses.

RESULTS

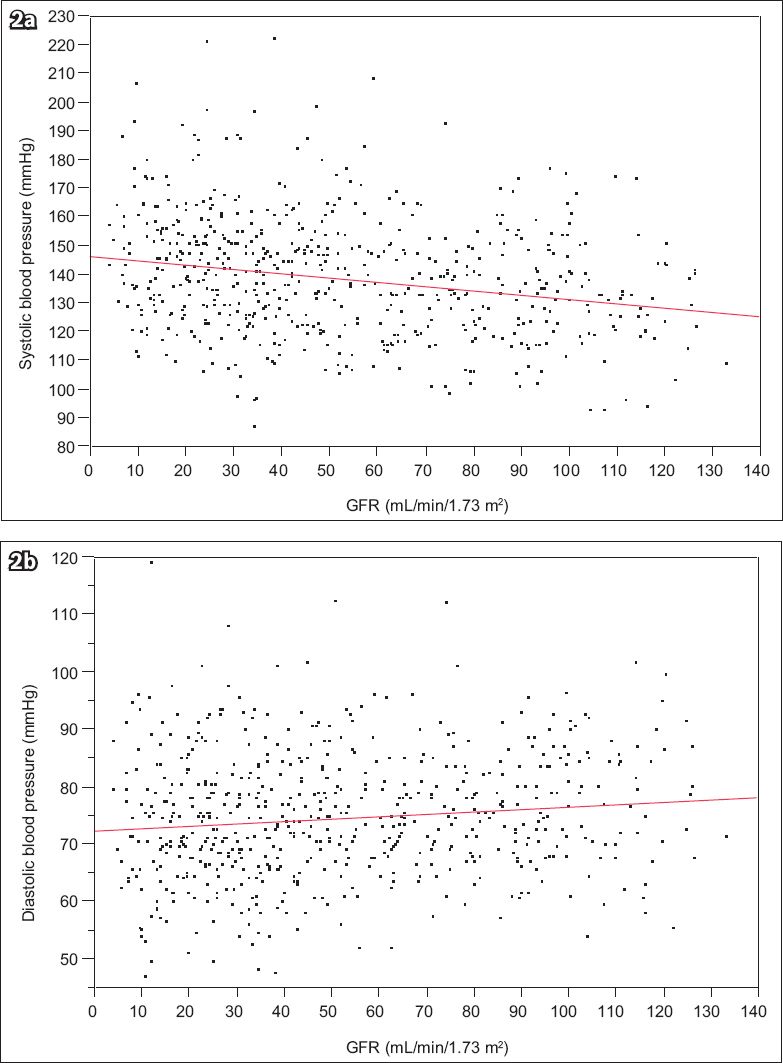

613 patients (55.1% male; 74.7% Chinese, 6.4% Indian, 11.4% Malay; 35.7% diabetes mellitus) with a mean age of 57.8 ± 14.5 years were recruited. Mean SBP was 139 ± 20 mmHg, DBP was 74 ± 11 mmHg, serum creatinine was 166 ± 115 µmol/L and GFR was 53 ± 32 mL/min/1.73 m2. At a lower GFR, SBP increased (p < 0.001), whereas DBP decreased (p = 0.0052). Mean SBP increased in tandem with the number of antihypertensive agents used (p < 0.001), while mean DBP decreased when ≥ 3 antihypertensive agents were used (p = 0.0020).

CONCLUSION

Different targets are recommended for each BP component in CKD patients. A majority of patients cannot attain SBP targets and/or exceed DBP targets. Research into monitoring and treatment methods is required to better define BP targets in CKD patients.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical practice guidelines vary in their recommended blood pressure (BP) targets for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).(1-4) Guidelines in a report by the Eighth Joint National Committee recommend a conservative goal of < 140/90 mmHg, with an emphasis on adjusting goals depending on age and comorbidities.(4) United States National Kidney Foundation (US NKF) guidelines, however, recommend a target BP of < 130/80 mmHg for CKD patients, with a further goal of < 125/75 mmHg for patients with proteinuria > 1 g/day, especially if diabetes mellitus is the cause of CKD.(1,2) Many patients with CKD require multiple antihypertensive agents to attain control.(5) It has also been noted that, in practice, many patients given treatment and medical attention are unable to attain BP goals in outpatient clinics, even in the clinical trial setting.(5,6) As clinical practice guidelines provide varying recommendations for different categories of patients, the stated BP targets are controversial.(5,7,8) Additionally, some have argued that the lower BP targets recommended for CKD patients are an extrapolation from pre-existing studies and not supported by strong clinical trial evidence.(1,2,9) Nonetheless, the US NKF guidelines have been very influential in nephrology practices, and many CKD programmes aim to achieve the lower general target of < 130/80 mmHg.

Regardless of practice guidelines, individual physicians differ in their preferences, beliefs, practices and patient types. In light of this controversy, this study examined the profile of BP components and antihypertensive agent usage in a multiethnic Asian population with stable CKD. The target population was patients in an academic, nephrology, tertiary referral practice in Singapore; to the best of our knowledge, the profile of such a population is still unclear.

METHODS

Data was taken from a cross-sectional observational study on serum cardiac biomarkers in CKD patients (NKFRC/2011/07/21). Outpatients with stable CKD at National University Hospital, Singapore, were prospectively recruited. Stable CKD patients were defined as those with variability of serum creatinine levels < 20% (taken more than three months apart) and who were diagnosed with CKD as defined by the US NKF guidelines.(10) At our institution, patients identified as having CKD had the following characteristics for more than three months: estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2; better GFR, but with evidence of urinary abnormalities; or abnormalities of the kidneys on imaging. All patients with available BP readings were included. Mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) levels were measured using automated manometers (DINAMAP; GE Healthcare, Singapore) according to clinical practice guidelines, with an average of at least two readings per patient.

Standardised serum creatinine was assayed and GFR calculated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation.(11) The study population was classified by CKD stages according to their GFR. Data was presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (25th–75th percentile) or frequency (percentage), where appropriate. BP and antihypertensive medication profile was examined using univariate analyses via standard statistical tests. A p-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

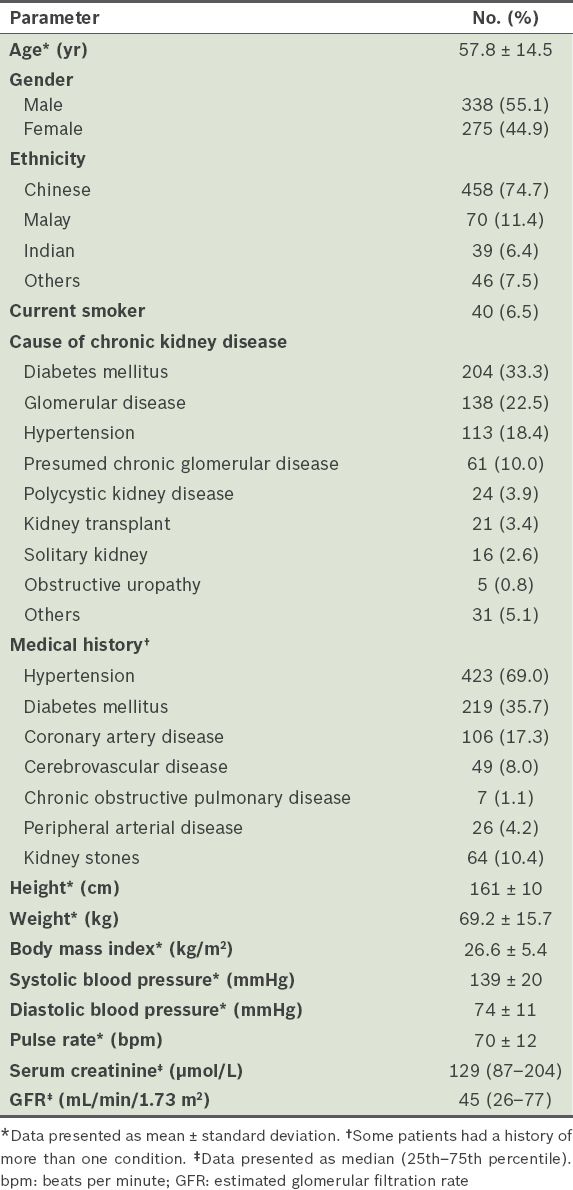

A total of 613 patients were included; the majority were male (55.1%) and of Chinese ethnicity (74.7%), with a mean age of 57.8 ± 14.5 years (

Table I

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (n = 613).

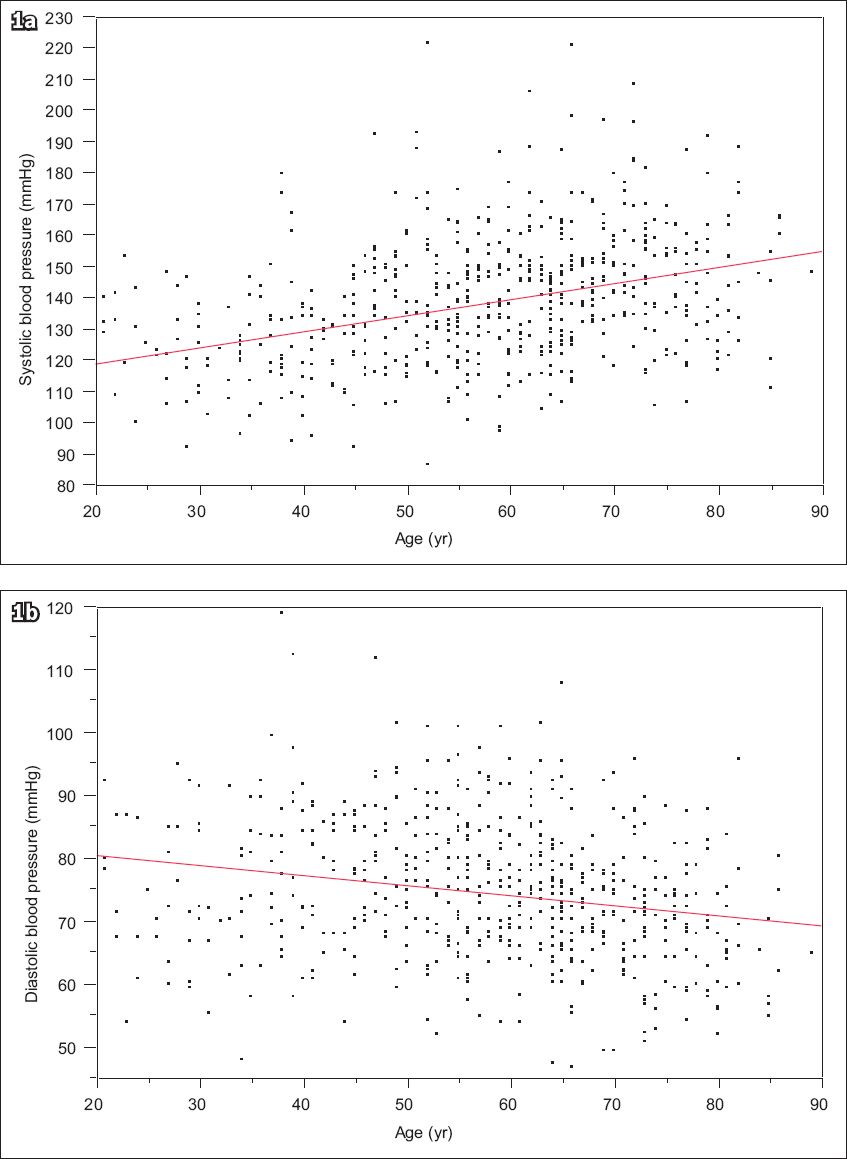

The mean SBP was 139 ± 20 mmHg, DBP was 74 ± 11 mmHg, serum creatinine was 166 ± 115 µmol/L and GFR was 53 ± 32 mL/min/1.73 m2. With increasing age, SBP increased (108.9 + 0.51 × age, p < 0.001), but DBP decreased (83.6 – 0.16 × age, p < 0.001) (

Fig. 1

Scatter graphs show mean (a) systolic and (b) diastolic blood pressure, by age.

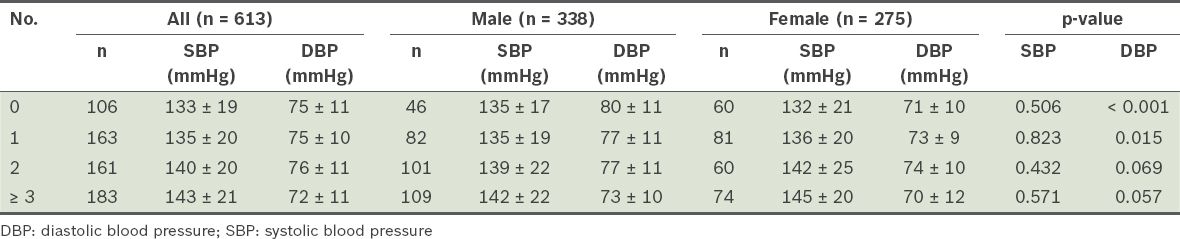

Table II

Mean blood pressure, by number of antihypertensive agents used and gender.

Fig. 2

Scatter graphs show mean (a) systolic and (b) diastolic blood pressure, by estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

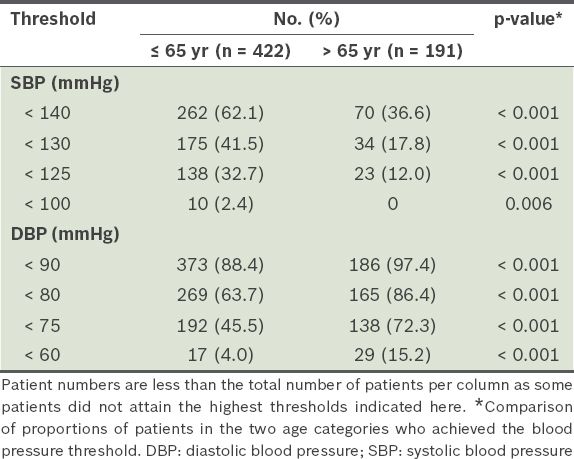

Patients with diabetes mellitus had a higher mean SBP (144 ± 21 mmHg vs. 136 ± 20 mmHg; p < 0.001) and DBP (76 ± 11 mmHg vs. 72 ± 11 mmHg; p < 0.001) compared to those who did not. Patients with a prior diagnosis of hypertension had a higher mean SBP (142 ± 20 mmHg vs. 131 ± 19 mmHg; p < 0.001) but similar mean DBP compared to those who were not diagnosed with hypertension. Patients diagnosed with coronary artery disease had a higher mean SBP (137 ± 20 mmHg vs. 133 ± 20 mmHg; p = 0.0027) but a lower mean DBP (72 ± 11 mmHg vs. 75 ± 11 mmHg; p = 0.0023) compared to those who did not have the diagnosis. The SBP of the 191 patients aged > 65 years was proportionately lower than that of younger patients as SBP thresholds decreased; the converse was observed for DBP (

Table III

Proportion of patients who attained blood pressure thresholds.

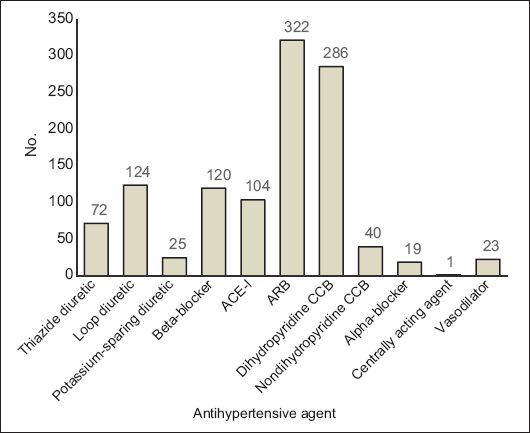

A total of 1,136 antihypertensive agents from 11 types of medications were prescribed. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers were the most commonly prescribed antihypertensive agents (34.4%, n = 391), with 35 patients on both an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) and angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). The distribution of antihypertensive agents used is shown in

Fig. 3

Chart shows distribution of antihypertensive agents used. ACE-I: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin-receptor blocker; CCB: calcium channel blocker

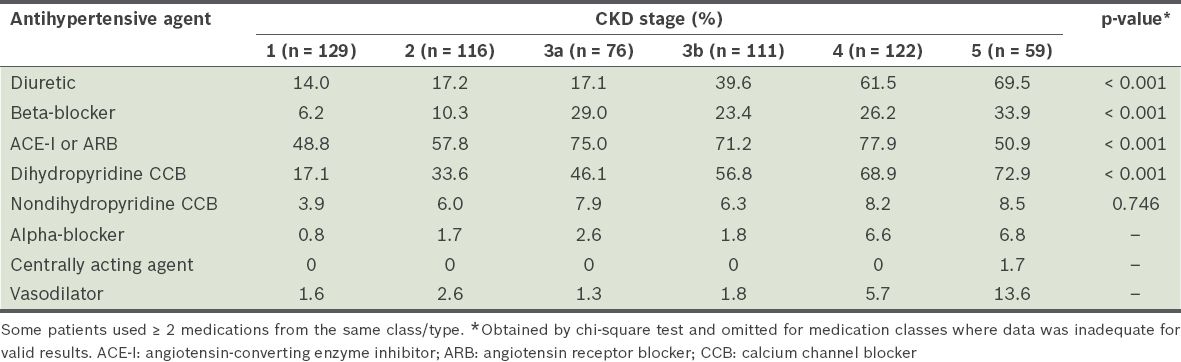

At higher CKD stages, more patients were on diuretics, beta-blockers or dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCB) (

Table IV

Distribution of antihypertensive agents used, by chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage.

The most commonly prescribed medications were: losartan (178/426, 41.8%), an RAAS blocker; atenolol (54/120, 45.0%), a beta-blocker; amlodipine (187/326, 57.4%), a dihydropyridine CCB; furosemide (122/221, 55.2%), a diuretic; and prazosin (10/19, 52.6%), an alpha-blocker. Only one patient was on the central agent methyldopa, 23 patients were on the vasodilator hydralazine, and 15 patients were on both dihydropyridine and nondihydropyridine CCBs.

DISCUSSION

The most important therapeutic step in the general retardation of CKD progression is the management of BP to within target levels. However, different clinical practice guidelines recommend varying therapy targets.(1-4) Using an initial SBP target of < 140 mmHg, the present study on stable CKD patients found that only 62.1% of patients aged ≤ 65 years and considerably fewer older patients (36.6%) achieved the target, although the study population underwent regular outpatient nephrology clinic follow-up. The overall attainment was similar to that of a large US cohort study.(6)

It was unsurprising that a large proportion of younger patients did not achieve the SBP target despite being on follow-up.(5) This may have been due to an inadequate number, type and dose of antihypertensive agents. Another possibility is that younger patients with better kidney function did not undergo dietary sodium restriction and diuretic therapy.(12) SBP targets are harder to attain in older participants, in whom widening of pulse pressure may occur after DBP levels are lowered in the course of treatment.(13) Studies have shown that excessively low DBP may be associated with increased morbidity and mortality; therefore, it is important to consider BP targets for individual patients in association with age, comorbid conditions and risk of falls.(6,14) In our cohort, more than a quarter of the elderly patients (age > 65 years) had SBP < 140 mmHg and DBP < 70 mmHg, which are associated with an increased risk of mortality in CKD patients.(6) Since the general aim was to reduce the risk of CKD progression and mortality, it is important to note that widened pulse pressures are also associated with end-stage renal disease.(15) In younger patients, it can be argued that more aggressive goals and treatments can be entertained to avoid end-stage kidney failure and a lifetime of dialysis. Moreover, more intensive BP control is not necessarily associated with increased morbidity.(16) Further randomised controlled trials are needed to clarify treatment targets for each component of BP in CKD patients.(5)

Another issue with the use of BP targets is the monitoring of BP.(17) In the outpatient clinic, BP readings are often inaccurate for a variety of reasons, and hence data collected outside a clinical trial setting may contain relatively higher readings,(17) compounding the mortality risk. BP readings may be lower given adequate time and equipment, as well as appropriate personnel training and the assignment of the best person to the task.(18) At our institution, there was a risk of obtaining incorrect blood pressure readings despite the presence of dedicated and trained research personnel using regularly calibrated automated manometers for measuring BP.(18) However, taking the average of several BP readings from a relatively large cohort reduced the risk of inaccuracy. Moreover, data collected in this study was similar to that observed in other CKD cohorts.(13,15) Some would argue that adding 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring may help to identify at-risk individuals and further improve the management of BP targets.(19) However, it was also noted that most of the major clinical trials on hypertension only used ambulatory (office-based) BP(19) and, for reasons of cost and convenience, nephrology clinics and practice groups in Singapore currently use office-based BP levels for management, except in cases of clinical uncertainty (masked or 'white-coat' hypertension).

The type of antihypertensive agent prescribed is typically dictated by indications for its use and physician preferences. RAAS blockers are widely used in earlier stages of CKD, but their usage falls significantly at Stage 5 CKD, presumably due to the potential problem of hyperkalaemia and concerns that an excessive reduction in GFR may contribute to it. Conversely, diuretic usage increases from Stage 4 to Stage 5 CKD, in keeping with the likelihood that more severe fluid overload or oedema with progressive kidney disease requires therapy intensification. Dihydropyridine CCB usage is relatively similar at all stages of CKD. Overall, proportionately more antihypertensive agents are used at Stage 5 CKD.

The specific medications used in our institution are, typically, dictated primarily by indications and partly by available formulary, as a result of open market tenders. Generally, medications for which generic versions are available are prescribed more frequently. The most commonly used ARB is losartan, followed by irbesartan, telmisartan and valsartan. The most frequently prescribed ACE-I is enalapril, followed by lisinopril, perindopril and ramipril. As many patients with CKD also have coronary artery disease and ischaemic heart disease complicated by left heart failure, carvedilol and bisoprolol are often also prescribed. The most frequently prescribed beta-blocker was atenolol. However, it has been reported that metoprolol may be preferable, especially in cases of more advanced kidney failure, as atenolol is cleared by the kidneys and may be associated with heart block.(20) This may not necessarily improve mortality; another retrospective cohort study showed that elderly patients (> 75 years) who were prescribed atenolol had a reduced risk of mortality compared to patients prescribed metoprolol tartrate, yet had similar risks of hypotension and bradycardia.(21) Amlodipine is the most commonly used dihydropyridine CCB to a considerable extent, followed by nifedipine. For nondihydropyridine CCBs, typically prescribed for additional blood pressure control and as an adjunct to reduce proteinuria,(1,22,23) more patients were on diltiazem than verapamil. The risk of or known coronary artery disease in patients usually precludes the use of verapamil, as it is associated with heart block when beta-blockers are concomitantly administered. Even though medications in the same antihypertensive class have similar mechanisms of action, the medications may have demonstrable differences in their ability to reduce morbidity and mortality.(24-26) Large practice data analyses would be helpful in future to examine potential advantages of certain types of medications.(25)

The present study had its limitations. As it was a cross-sectional descriptive study, there was a lack of outcome data on patient mortality and morbidity. Elderly patients who declined or were excluded from participation due to their inability to provide consent or venepuncture might have different BP levels and medications from those found in the study. Some patients may have been seen by medical providers in other institutions and had incomplete medication information, particularly less educated patients who were not able to describe their entire medication list. Another major limiting factor was the lack of standardised data on the degree of albuminuria in patients, which may have impacted the aggressiveness of the prescribing physician's treatment targets and antihypertensive prescriptions. No urine samples were collected previously because the data was originally for a serum biomarker study. In our institution, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, albumin-to-creatinine ratio or 24-hour urine collections are ordered at the attending physician's discretion; therefore, collected data is not standardised in format and chronology. Nevertheless, the majority of patients on follow-up at the kidney disease clinics usually have clinically significant proteinuria > 0.5 g/day, as the institution is a tertiary referral centre. The strengths of our study were its prospective nature and the fairly large study sample of multiethnic Asian patients with stable CKD. With this sample, a cross-sectional examination could be conducted on BP levels attained for each BP component, following therapy principally guided by nephrologists.

In summary, many of our patients failed to attain the target BP, but a significant proportion of them may be considered higher risk if their SBP and DBP are taken into account. An increase in the number of antihypertensive agents used resulted in divergence in the achievement of targets. Further research to improve methods of monitoring and treatment is required to better achieve targets, and link BP parameters to GFR decline and mortality in Asian CKD patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The project was funded by a National Kidney Foundation, Singapore, research grant awarded to Dr Boon Wee Teo (NKFRC/2011/07/21). Mr Qi Chun Toh, Mr Zichao Chen and Ms Hwee Min Loh from the National University Health System, Singapore, recruited the participants, collected the data and prepared the database. We acknowledge the study investigators, Dr Martin Lee, Prof Evan Lee and Prof Vathsala of the National University Health System Nephrology Clinical Research Group, Singapore, who actively recruited participants for this study.