Abstract

A congenital lip sinus is a rare condition that has been reported to occur in both the upper and lower lips, either in isolation or in association with congenital deformities such as a cleft lip and palate in Van der Woude syndrome. The prevalence of lower lip sinuses has been estimated to be about 0.00001% of the white population. Upper lip sinuses are even more uncommon. To date, there have been several case reports of upper lip sinuses and fistulas, but no similar cases have been described in Singapore. We herein report a case of congenital upper lip sinus presenting as a recurring upper lip abscess and review the current literature on this condition.

INTRODUCTION

A congenital lip sinus is a rare condition. This epithelial anomaly has been reported to occur in both the upper and lower lips, either in isolation or in association with congenital deformities such as a cleft lip and palate in Van der Woude syndrome. The estimated prevalence of lower lip sinuses is about 0.00001% of the white population,(1,2) but upper lip sinuses are even rarer. To date, only several cases of upper lip sinuses and fistulas have been reported, but no similar cases have yet to be described in Singapore. We herein report a case of congenital upper lip sinus presenting as a recurring upper lip abscess and review the current literature on this condition.

CASE REPORT

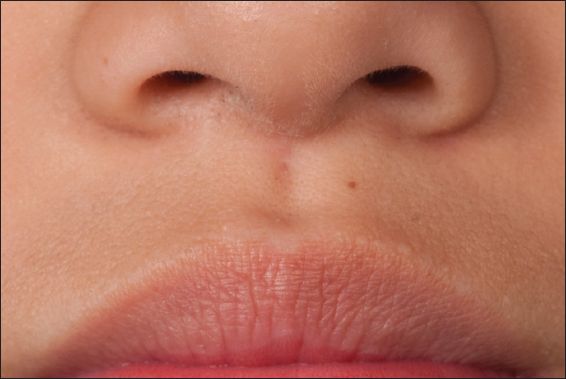

An 11-year-old Chinese girl presented with recurrent upper lip swelling after repeated incision and drainage procedures. Besides a history of asthma, she appeared well with no other significant medical history. An examination revealed swelling of the upper lip with a punctate opening in the midline of the upper lip, 3 mm below the base of the philtrum (

Fig. 1

Photograph shows a midline sinus on the patient’s upper lip.

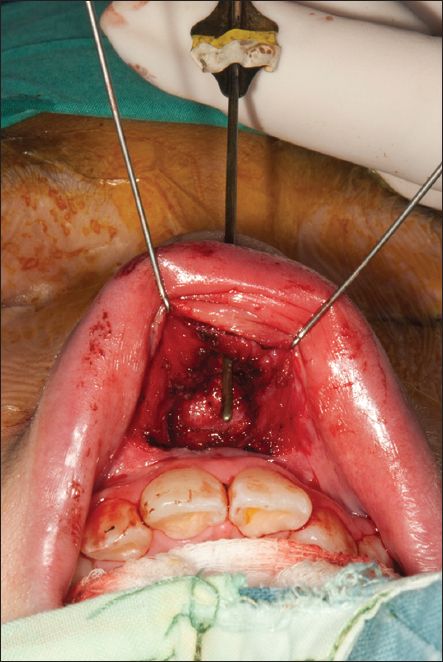

After the initial infection was resolved, excision of the congenital sinus tract was scheduled. Intraoperatively, a fistula probe was inserted into the opening on the cutaneous surface of the upper lip. It was found that the opening ended blindly, with no communication with the intraoral cavity (

Fig. 2

Photograph shows a fistula probe being inserted, revealing the blind-ending sinus.

Fig. 3

Photograph shows the sinus tract being excised via an upper buccal sulcus incision.

Fig. 4

Photograph shows the resected specimen.

Histopathological examination of the 1 cm × 0.4 cm specimen showed a sinus tract that was 0.3 cm in maximum diameter with a slightly dilated blind end measuring 0.3 cm. The blind end contained keratinous debris lined with keratinising stratified squamous epithelium associated with sebaceous glands. There was evidence of surrounding chronic inflammation. Postoperative follow-up at five months revealed a small inconspicuous scar on the upper lip (

Fig. 5

Photograph of the patient’s upper lip at five months shows a small inconspicuous scar with no recurrence of the lip sinus.

DISCUSSION

Although the mechanisms involved in the formation of congenital upper lip sinuses are incompletely understood, there are three main theories for their aetiology. The invagination theory(3-5) proposes that upper lip sinuses are formed by failure of ectodermal invagination of the nasal placodes during the frontonasal process. The merging theory(6,7) proposes that the sinus is due to aberrations in the normal mesodermal merging process. The fusion theory(8-10) proposes a failure of complete fusion between the frontonasal and maxillary processes.

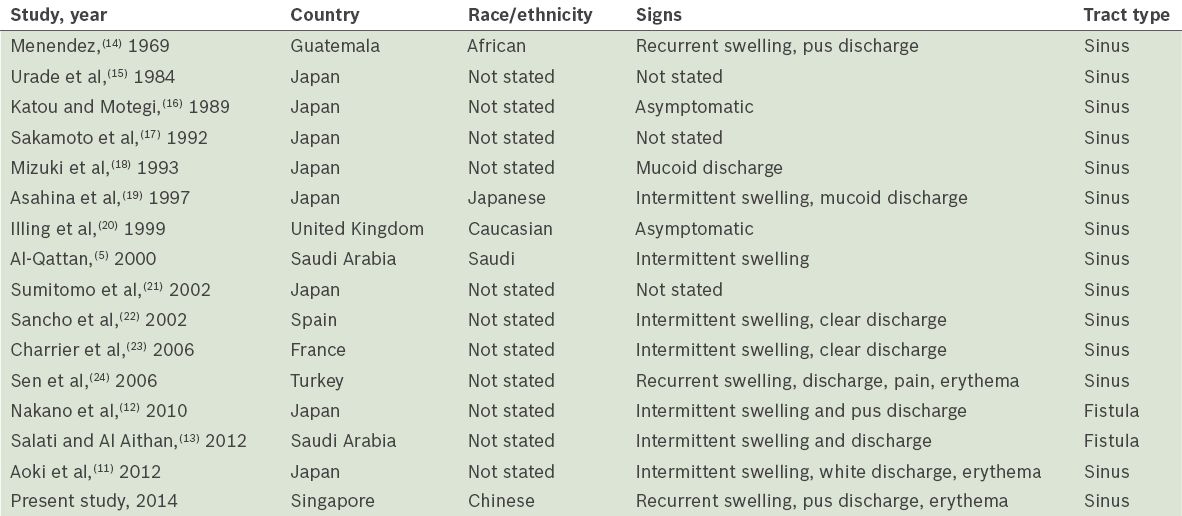

Because this condition is so rare, much of our knowledge is based on details of individual case reports. Aoki et al, who developed a classification system for upper lip sinuses in 2011, reviewed and classified 31 upper lip sinuses into three categories: (a) Type I: midline sinus without accompanying anomalies; (b) Type II: midline sinus with accompanying anomalies; and (c) Type III: lateral sinus with or without accompanying anomalies. They found a female predilection in Type I upper lip sinuses (12/13 females).(11) Two separate reports by Nakano et al(12) and Salati and Al Aithan(13) both describe a congenital upper lip fistula in female children. Including our patient, there are now 16 cases of girls with isolated midline upper lip sinuses or fistulas. Interestingly, further review of the reported cases (

Table I

Review of published reports of upper lip sinuses and fistulas without congenital anomalies.

In the management of this rare condition, a high index of suspicion is necessary when a patient presents with recurrent upper lip swelling and discharge. Recurrent infections occurred in 25% of the reported cases. A thorough history and examination should be conducted, looking specifically for congenital pits on the lips and associated congenital abnormalities. Van der Woude syndrome is an autosomal dominant, inherited condition known to be associated with cleft lips, palate and lower lip pits; however, upper lip sinuses are not known to be associated with any particular mode of genetic inheritance. In this case, the patient’s family history also did not reveal any similar conditions, which suggests that the anomaly may be spontaneous rather than inherited.

In conclusion, surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment for upper lip sinuses, especially in patients with repeated infection. Complete delineation and excision of the tract is required, as incomplete excision can lead to recurrences with resultant scarring and cosmetic deformities. To minimise scarring, excising the sinus from its blind end to the skin punctum via an upper buccal sulcus approach may be considered. This approach also gives the physician better access to excise the entire sinus tract and the surrounding chronically inflamed tissue.